WHEN I think of Easter in Greece, I think of dyed red eggs, euphoria and feasting. I also think of mutant incense, terrier rebellion and ‘Ecclesiastical Knee Syndrome’.

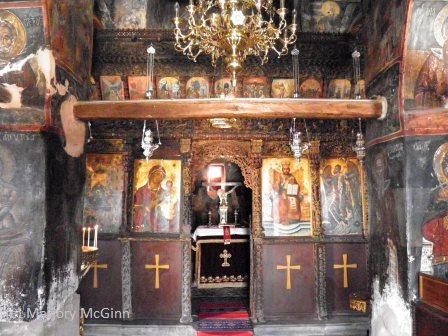

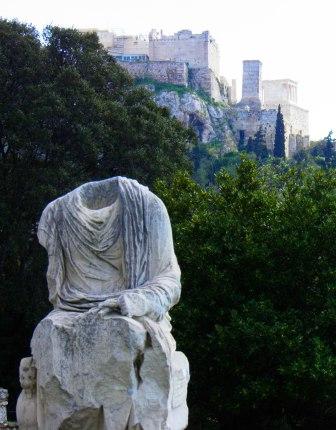

The Holy Week (Megali Evdomada) is this week, and it’s the most significant date in the Greek calendar. From all my many years of visiting Greece, Easter leaves indelible memories for its sense of drama and anticipation. Much of the drama is supplied by the daily church services that are like small one-act plays of varying intensity and nail-biting climaxes that progress the story of Easter, which seems unique to the Orthodox Church. Even if you’re not religious, it’s a wonderful chance to see Greeks at their most reverent, and at their colourful best, with plenty of pomp, circumstance and sometimes unplanned slip-ups showing that the best rehearsed productions can be derailed.

When we were living in the hillside village of Megali Mantineia in the Mani (southern Peloponnese), the sombre Easter Friday service ran slightly amok when Wallace, our naughty Jack Russell terrier, disgraced himself, slipped out of our village house and raced along with the procession, turning a timeless ritual into a cross between a riot and a Crufts obstacle course for Jack Russells. The Friday service is the grand procession of the Epitafios, where a flower-decked bier, representing the crucified Christ, is carried through villages and cities everywhere in Greece, and is a magical event to witness.

Our village procession started at the main church, went up to the graveyard, so the papas could offer prayers for the dead, and looped back along village lanes towards the church again, with the papas and elders at its head. Wallace managed to invade it early on. I don’t think the villagers had seen anything quite like the hyperkinetic Wallace, weaving his way through the procession, a blur of white fur, and retrieving him required a bit of a miracle. It became one of the chapters in my first memoir Things Can Only Get Feta.

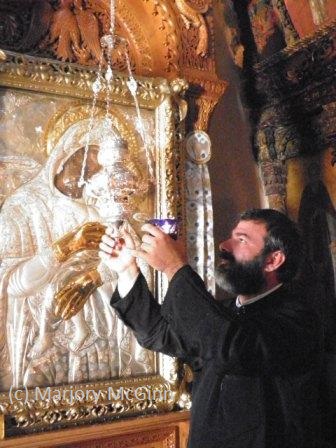

The services in this Easter week are awe-inspiring for their organisation, their props and those amazing psaltes, chanters, who advance most of the service and seem tireless. Even during the tough economic crisis, no detail was ever spared and for that you can only admire the Greeks. Yet sometimes nerves get the better of everyone. On one of the Thursday services in our first year in the Mani, which is a particularly long and devotional service, the poor deacon, standing beside the local papas, turning over the pages of the old hymn book, overlooked the massively smoking censer in his hand.

“The incense started off with fragrant puffs but quickly increased to billowing acrid clouds that shrouded the first few rows of seating. We started coughing and choking. If this had been an aeroplane, oxygen masks would have dropped from the ceiling by now.” (Things Can Only Get Feta, chapter 25).

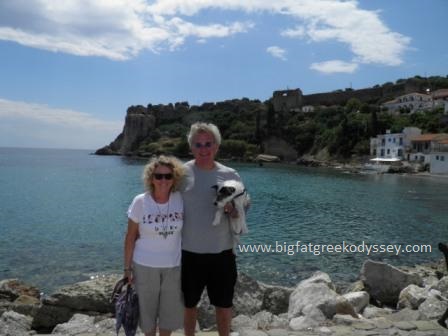

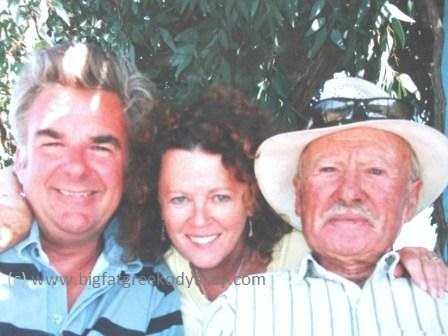

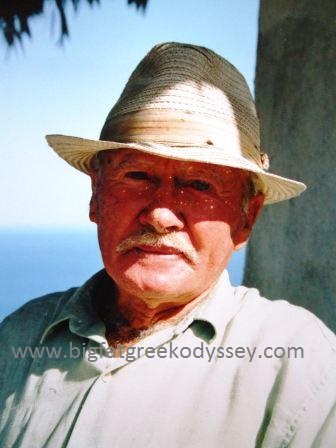

Easter Sunday with the family who featured in Marjory’s second travel memoir, Homer’s Where The Heart Is

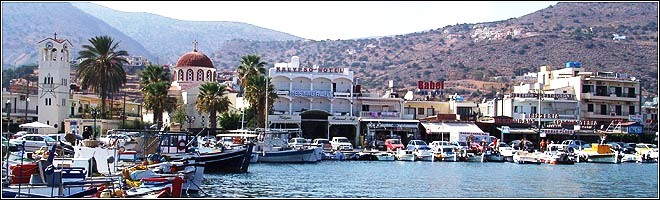

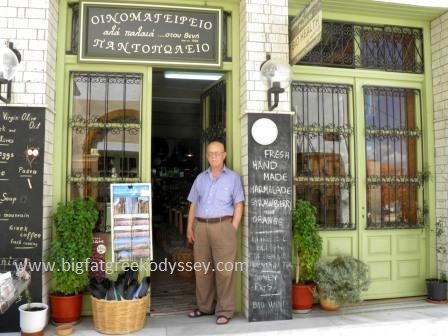

I have experienced Easter in many locations in Greece, from tiny islands to cities. In each location, the church services have been handled with aplomb. I have also found the same level of hospitality and kindness from locals, with many invitations to share the traditional Sunday roast with an extended Greek family. One of my first Greek Easters was in Crete, which I first visited in the 1970s on my first long odyssey to Greece. I had been living and working in Athens, but before I left I had taken a few weeks’ break in Crete with a friend. We were offered a tiny holiday house by an Athenian colleague. It was opposite the beach in a completely authentic, untouched area of the northern coast, east of Hania. While the area is, sadly, unrecognisable now from what I remember then, it was a glorious piece of old Greece, with a few nearby houses, a taverna across the road, a deserted beach and not much else.

My friend and I had planned to have a quiet Easter as we knew no-one there and we knew very little about Easter customs and protocol. On Sunday morning, however, there was a knock at the door. It was the farmer who lived up the hill behind us. He vibrantly announced Christos Anesti which I knew meant, Christ Is Risen, the salutation after the Saturday night service. He told us that for the traditional Sunday feast he was roasting one of his lambs and that we must come and join his family. There was no way we could refuse. He insisted.

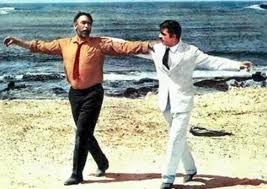

So we went up to his house, where the lamb was turning slowly on a spit outside and the olive groves around us were filled with succulent meaty, herby aromas. A big family had gathered: grandparents, kids, everyone excited to be eating a proper meal after weeks of the strict Lenten fast. We had lunch at a long table surrounded by these wonderful, big-hearted people, whom I could barely talk to as I spoke only limited Greek then. Somehow we managed okay and enjoyed all the conviviality, the laughter and lusty cracking of the dyed eggs, an ancient Orthodox ritual that symbolises eternal life and becomes a contest to see who can crack everyone else’s eggs without cracking their own.

Jim and Marjory enjoying the egg-cracking contest at a memorable supper with their Kalamatan friend Kostas and his lovely family

This Sunday lunch experience was during my first long but youthful foray into a foreign culture and I had never come across such inclusiveness and kindness before from strangers, even having grown up in friendly, knock-about Australia. This was unique and the memory has lingered.

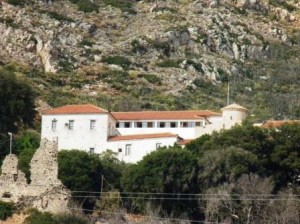

Every Easter I have spent in Greece has taught me something more about the Greek spirit, the sense of filoxenia, hospitality and this unique culture. It has also offered me some unexpected, occasionally humorous, outcomes, and the odd devious medical problem which Jim and I came across during Easter, 2014, for our second odyssey in southern Greece, in Koroni. We had decided that we would set ourselves the task for Lent of going to every evening church service of Megali Evdomada, in a different church each night, which we had never done before.

We made it through the first part of the week no trouble, but by Thursday, which is a very long service, nearly three hours, depicting Christ’s crucifixion, we were starting to run out of steam. Jim developed a painful problem which he called Ecclesiastical Knee Syndrome (EKS) because there is so much standing up and sitting down during Greek services, and at this time of year, churches are slightly cold and bone-numbing.

“The service was longer than I ever remembered any to be, full of Greek I couldn’t decipher, and as I glanced around the church I saw many Greeks looking pale and wilted, with many of the men discreetly slipping outside for a quick cigarette in the cool evening air. As foreigners, we felt the need to stay, and endure, lest we be considered slightly soft or disinterested. Nine-thirty came and went in a strange agony of chanting, incense and a babble of high Greek. Unlike Jim, after a while I welcomed EKS, and every opportunity to stand up and feel my legs like an economy passenger on a long-haul flight to Australia which is what the service began to feel like.” (Chapter 2, A Scorpion In The Lemon Tree).

But the Thursday service actually ended with a surprise, slightly controversial, climax that was worth the wait, despite distressed knee cartilage. And it was a dramatic lead-up to the finale of this week, which is the Saturday service. This is something that everyone should experience once in their lives, which in the Orthodox Church represents the resurrection of Christ. And on a less illustrious level, it also represents the end of the Lenten agony for many devout Greeks, who have lived for six weeks on boiled greens and water, or near enough. It represents the end of an ecclesiastical marathon. I have experienced this Saturday service in Greek cathedrals and also in tiny island churches and it never fails to be affecting and inspiring.

The moment when the church is plunged into darkness at midnight and a single lighted candle is brought out of the sanctuary by the papas and its light slowly shared to every other member of the congregation until the church is luminescent is a simple, yet thrilling spectacle. And if you are lucky enough to also hear a particularly good rendition of the hymn Christos Anesti (Christ is Risen) then you are truly blessed.

Happy Easter!

Καλη Aνάσταση! (Kali Anastasi) Have a good resurrection, as they say in Greece!

(To hear the Vangelis rendition of Christos Anesti performed by Greek actress, Irene Pappas, please click on the link below.)

For more information about Marjory’s three travel memoirs about living in Greece during the crisis, go to the books page on the website www.bigfatgreekodyssey.com or the books page on Facebook www.facebook.com/ThingsCanOnlyGetFeta

The third book, A Scorpion In The Lemon Tree is available on all Amazon sites:

To buy either of the first two books please click on the Amazon links below:

Messages are always welcome. Thanks for calling by. x

© All rights reserved. All text and photographs copyright of the authors 2016. No content/text or photographs may be copied from the blog without the prior written permission of the authors. This applies to all posts on the blog.