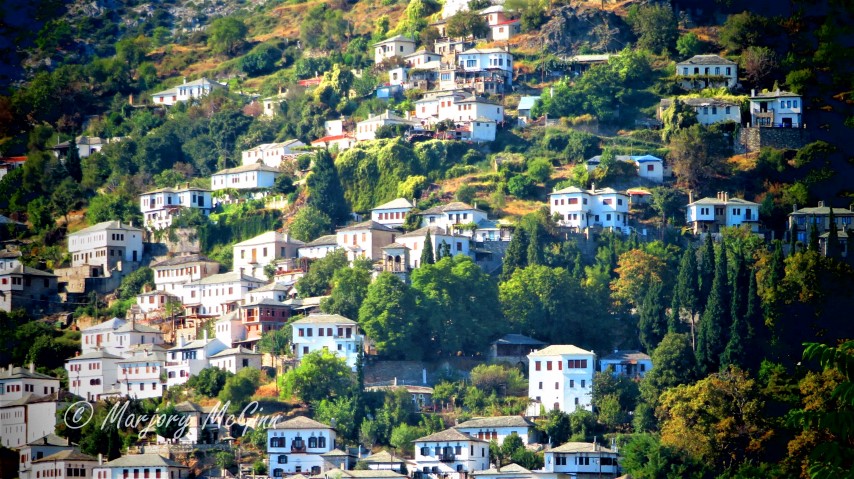

WHEN Jim and I moved to the Mani region of southern Greece for our mid-life adventure during the country’s economic crisis, we set out to live as Greek a life as possible. We went to church services in the hillside village where we first lived, and also to the vibrant saints’ day feasts, held outdoors with lashings of barbecued goat and village wine.

We tried everything, with various degrees of success – and sometimes mild disgrace – when, for example, we didn’t understand some of the Byzantine rituals of the Greek Orthodox Church and made a few gaffes. We tried olive harvesting (back-breaking!), got in a lather with traditional soap making, and even tried the peculiar delicacy tsikles (small pickled birds) to please a neighbour (never again!).

The point of our Greek odyssey was to do (often crazy) things we’d never done before, and try a new way of life, without most of the cultural norms and cliches of Britain. Christmas had been a welcome revelation in the first year. More low-key and reflective with less of the Christmas hysteria of the UK: the manic shopping, the house fronts decked out like the Blackpool illuminations. Not that we’re knocking a British Christmas, but we’ve never been that into ‘festive-to-the-max’, unlike some British expats we met in Greece early on who were, and who complained bitterly that the Greeks “just can’t get Christmas right!”.

Whenever I heard that I used to do a mental high-five, looking forward to our first taste of seasonal serenity in our hillside village, where most locals were hard-working olive and goat farmers. So it would have been risky chopping down a ‘Christmas’ tree. And there was no need to tinselate our small Greek house into a rural glitter ball. As if! But villagers were there on the day, chapping on our door like the ‘wise men’, bringing us seasonal cheer, offering sweet biscuits, cans of oil and other treats.

In the lead-up to our second Christmas in this region, we were renting a different house, not far away, close to the Messinian Bay, a traditional Greek home with folky sofas and paintings. Our landlords, a convivial Greek couple, Andreas and Marina, called around to see us regularly and usually with ‘deliveries’ – food and household offerings in eccentric pairings I’d come to enjoy: broccoli and floor cleaner, cabbages and firelighters!?

One November afternoon the couple were on the doorstep, Marina with several bulging plastic bags and a basket with a red pointy hat sticking out. That should have alarmed us straight off! Marina rushed, bag-laden, past us into the house with her usual Greek proprietorial charm, while Andreas hung back at the door, chatting. The imminent olive harvest was very much on his mind because in rural areas the whirring sound of harvesting equipment trumps sleigh bells every time.

While we chatted, we forgot about Marina for a while until we became aware of furious scurrying and hammering going on behind us.

“What’s happening inside, Andreas?” I asked him, almost too scared to look.

He rolled his eyes and offered an Olympian shoulder shrug. “Marina has just decorated the house for Christmas.”

“What!?”

Jim and I spun around and walked into the open plan sitting room/dining room. Whereas it once looked atmospheric and Greek, which is how we liked it, the place now resembled Santas’s Grotto at a John Lewis store. A big red Santa was lording it over the dining table and tinsel was strung over paintings and across the top of the open fireplace. No health and safety in Greece. On every available surface: flashing Christmas lights, more santas in pointy hats, reindeer trundling across the coffee table and so forth. We gawped, feeling mildly ill. Even Wallace, our feisty Jack Russell terrier, trying to doze in his dog bed, had been fixed up with clip-on red ribbons and other festive embellishments.

“Here,” said Marina, thrusting two fluffy festive socks towards me. “For Christmas Day.”

“But Marina, it’s barely November. Too early for Christmas decorations, surely,” I pleaded.

Andreas shook his head. “I agree Marjory, but Marina LOVES Christmas, you have no idea!”

Oh yes I did! The living room – lit up and pulsating, lacking only a sound system for Christmas carols – told me so. Silent Fright came to mind!

“This old place looks better now, don’t you think?” she said, hands on hips like the presenter of a TV home makeover show. Except we felt like the teary owners you often see, pretending to be overjoyed with an unexpected vision of home-hell. In Marina’s mind, the theme park she’d whipped up was what she thought we craved, miles from home at this time of year. Ah, bless! She meant well, in that extreme kind of Greek way.

Jim and I laughed over it later and slowly began to dismantle some of her offerings, leaving a bit of tat in place and hiding the rest in the apothiki (storeroom), haggling over santas and sleighs, wondering which things Marina would be more likely to miss on her next visit.

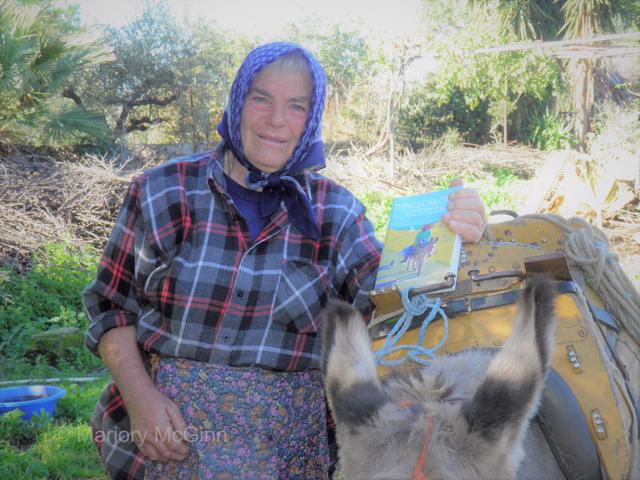

Whenever she came inside after that, her quizzical eyes strafed the room, doing a kind of mental inventory, but to her credit she never remarked on the adjustments. Meanwhile, with a developing artistic flair, she set about making countless Christmas wreaths wound through with fruit, veg and other Magpie finds, decorating everything from cat flaps to clapped-out welly boots, as pictured, top.

But it’s exactly what we came to Greece for. Wasn’t it!?

The story of our Greek Christmas first appeared in a slightly different form in my second memoir, Homer’s Where The Heart Is, which continues the funny, candid story of us attempting to live in Greece like locals, starting with the Amazon best-selling first memoir, Things Can Only Get Feta.

https://mybook.to/HomersWhereTheHeartIS

New novel

If you enjoyed reading my four Greek memoirs and my first two novels, A Saint For The Summer and How Greek Is Your Love?), set also in the Mani peninsula, Greece, you will love my latest novel, The Greek Proposal. This time I chose the wild Messinian peninsula nearby for this story of romance, mingled with mystery and family war secrets. It has a feisty heroine, Isla, two gorgeous suitors, plus a lovable sausage dog, Lou – small in stature, big on character! It also has a stunning location, near Koroni, inspired by the year we later spent living there.

The Greek Proposal: “A masterful piece of storytelling” “Terrific characters”. Five-star Amazon reviews.

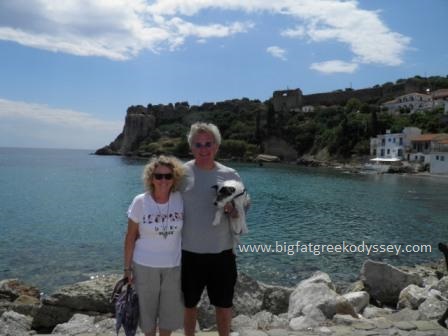

For more information about Marjory’s Greek memoirs and two novels set in Greece, please click on the Greek Books tab on her website https://www.bigfatgreekodyssey.com

Or on her Facebook author page: https://www.facebook.com/MarjoryMcGinnWrites

X (Twitter): www.x.com/fatgreekodyssey

Instagram: www.instagram.com/marjorywrites

Have a Merry Christmas when it comes, and thank you for reading Marjory’s blogs and books and for your ongoing support. The author always loves to hear from readers on her website and reviews of her books are also kindly appreciated.

Thanks for stopping by.

© All rights reserved. All text and photographs copyright of the author 2010-2025. No content/text or photographs may be copied from the blog without the prior written permission of the author. This applies to all posts on the blog.