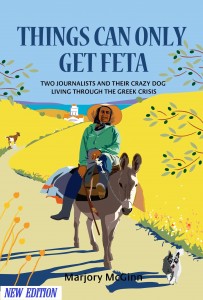

THIS month it’s 10 years since my first Greek travel memoir, Things Can Only Get Feta, was published and I’m thrilled to say the book is still going strong: a best-seller in various Amazon categories, despite a publishing drama early on. However, it has soldiered on with vigour and even found its way recently onto the syllabus of a Greek university course. But more of that later.

If you’ve followed my blog over the past decade, you’ll be familiar with how the book, about living in Greece during the economic crisis, came about. But if you’re just tuning in for the first time, in short: my husband Jim and I, and our famously bonkers Jack Russell terrier Wallace, left a Scottish village in 2010 for a mid-life adventure in southern Greece. It was during a British recession and a downturn in the newspaper industry, in which we both worked as journalists.

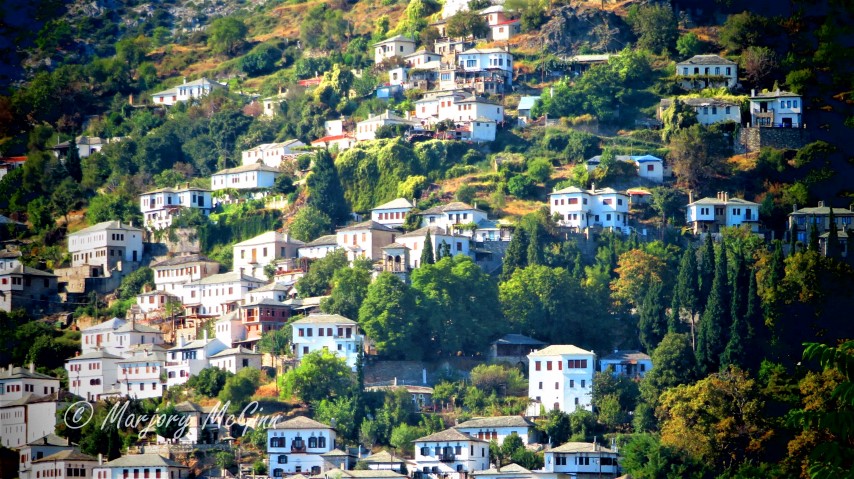

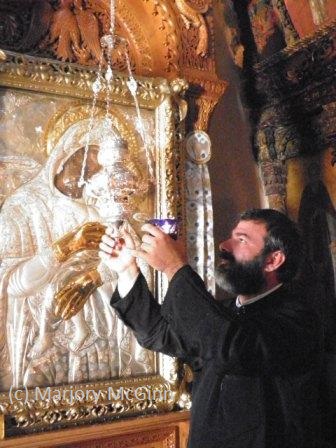

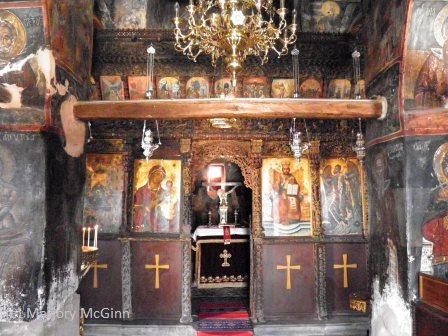

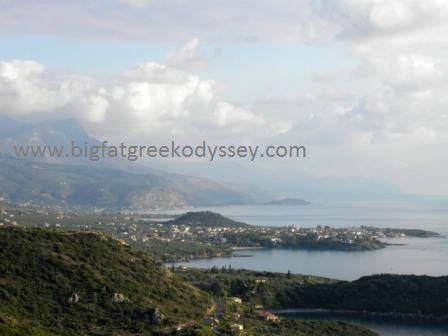

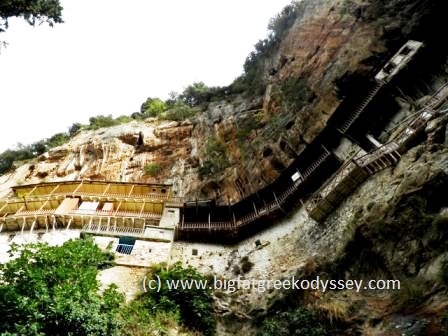

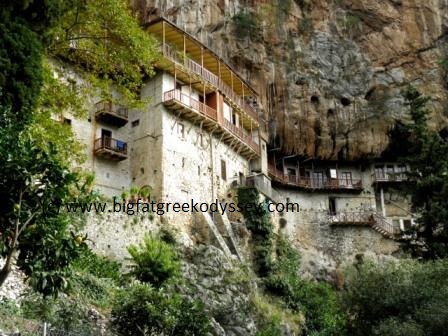

And what an adventure it turned out to be, settling in a rented stone house in a hillside village in the remote, wild Mani region. It was a working village, raw in places, sometimes well beyond our comfort zone but perfect for our aim of living a Greek kind of life while we freelanced for various publications in Britain and Australia to help fund our odyssey. Greece was on the brink of meltdown due to its devastating economic crisis of 2010. The country, with massive debts, had to accept a bailout from the EU and punishing austerity to go with it. An ideal time for journalists perhaps, but not for a trouble-free stay in beautiful Greece.

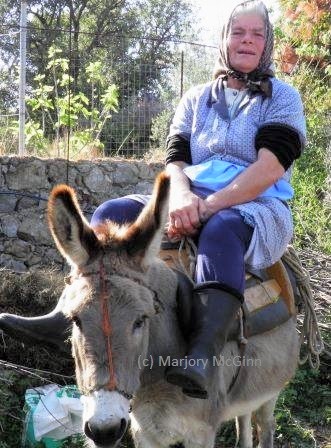

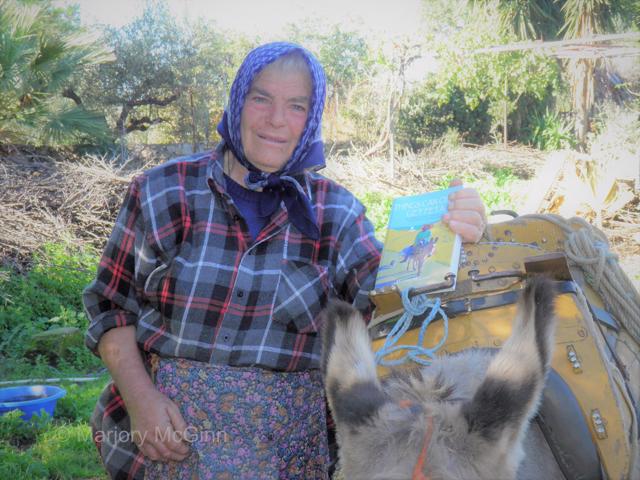

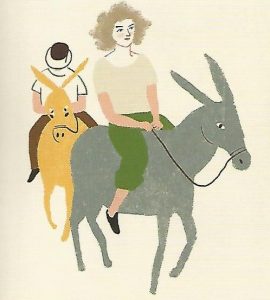

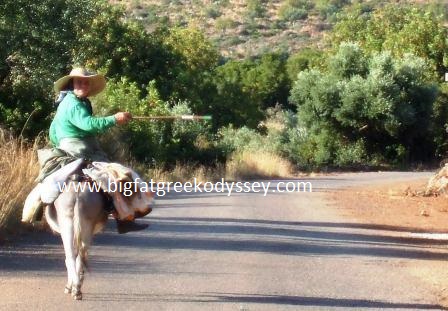

However, we went regardless and found ourselves in an ideal location, living amongst big-hearted goat and olive farmers. We made friends with many, particularly the inimitable Foteini, the eccentric goat farmer with her famously endearing taste for thick, clashing layers of clothing and rural mayhem. Ironically, it was my curious friendship with Foteini (pushing my imperfect Greek to its limits) that helped steer our path in the village. She also became an unlikely literary muse – who knew?! Her touching stories and her antics inspired me to start writing Feta, to record a rural way of life in the Mani peninsula (one of the three that hang down from the southern mainland) that I was sure was about to change forever.

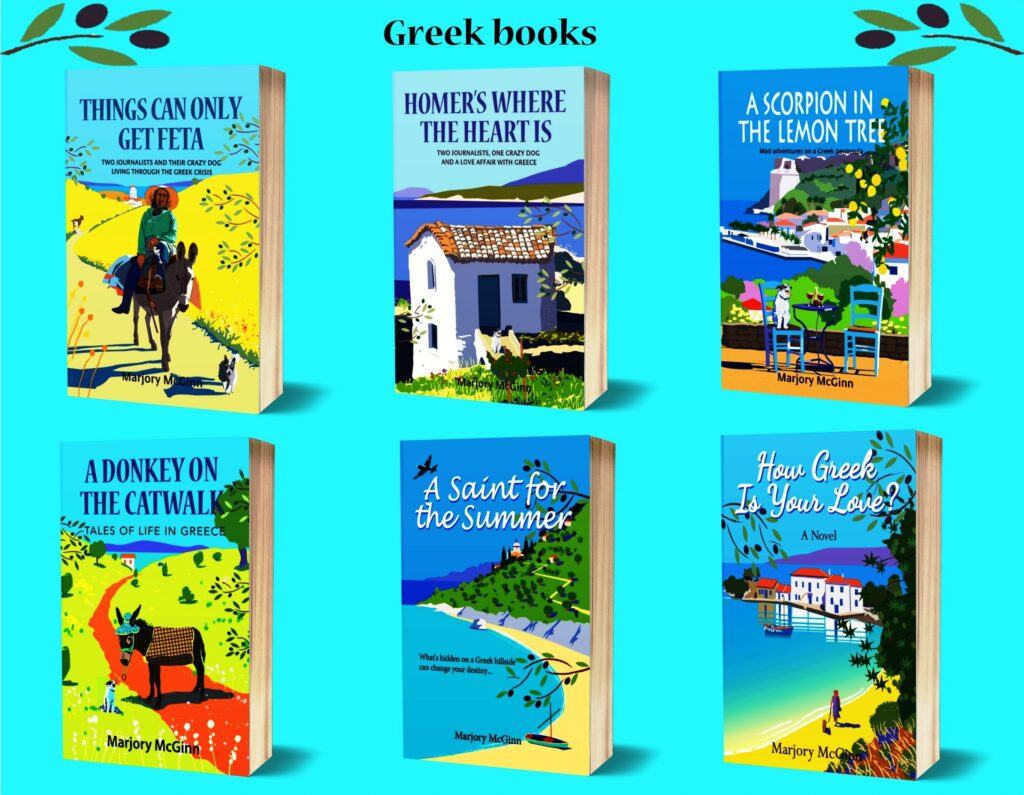

The first year in the village of Megali Mantineia, beneath the Taygetos mountains, exceeded all our expectations. It was challenging, fascinating, often hilarious, and sometimes downright frustrating. We dealt with macabre local customs, a health drama for Wallace, a hospital visit for Jim, critters (scorpions, lots!), eccentric expats, but mostly it was a lesson in surviving Foteini’s ramshackle farm compound, her strong mizithra goat cheese, and a slew of scatty, but endearing animals. At the end of the first year, we decided to stay longer in Greece, which grew to four years in all, living for the final year in the nearby Messinian peninsula, near Koroni. I wrote four best-selling books about our life in Greece, and two romantic suspense novels, also set in the Mani.

I started writing Feta in the freezing winter of 2010/11 in our stone house, my desk wedged up against the loungeroom window with a view of the snow-capped mountains. But I also had a view of the rickety back entrance of Foteini’s old village house, where she spent her evenings. Sometimes, she must have seen me at the window. Or perhaps she just sensed I was writing about our village antics, many of them hers, and she’d phone, particularly if she hadn’t seen us for a while. It was usually with the same humorous lament. “Ach, you’ve forgotten me already, koritsara mou (my girl)!” she’d say. “When are you coming for coffee at the ktima?”

The idea of sitting in Foteini’s draughty farm shack in foul weather beside a dodgy petrogazi (small gas cooker) didn’t always appeal. However, we did go now and then in winter, which I wrote about, including the memorable day Foteini came close to blowing up the shed.

I had plenty of material for a book, from the adventures and mishaps of the first year, and I continued to add to the narrative over the next three years. Things Can Only Get Feta was published in 2013 by a small London publisher, during a long intermission in Scotland before we returned to Greece again. From the beginning, Feta did very well and sparked great interest, particularly in Greece in the summer of 2013. After doing a phone interview with the editor (Sotiris Hadzimanolis) of the Australian Greek newspaper Neos Kosmos, about our life in Greece and the book, Sotiris filed a similar piece to a Greek news outlet and from there, the story of our exploits went slightly viral.

Versions of it turned up in a slew of Greek publications and internet news sites with variations of the headline: “Scottish journalist besotted with Greece”. While there are many authors today, focusing on a much trendier, revitalised Greece post-crisis, 10 years ago the story of a foreigner having a love affair with Greece in turmoil was certainly more unusual. More than that, it struck a chord with long-suffering Greeks who had hitherto heard nothing but negative, often beat-up, reports in the international media. There were harsh criticisms of the country’s fiscal attitudes and work practices, whereas the story about Feta was a good-news story.

We had scores of messages sent to our website with notes of thanks for my Greek ‘ardour’ and my favourite comment of all time is still: “For your information, Greece loves you back.”

However, despite the book’s success, two years later, while Jim and I were now living in Koroni, I had a falling-out with my London publisher when he seriously broke the terms of our contract. (In publishing, be careful what you wish for!) Rather than allow the book’s success to be sabotaged, I legally forced the return of the book rights to me, and republished it myself in a very short time. This was no small feat, working on an old laptop computer from a hillside house with just a mobile phone and poor wi-fi, or often, no wi-fi. But nevertheless, once re-published the book had a fresh gust of wind under its wings and continued to do very well. Not long afterwards, I published the second memoir, Homer’s Where The Heart Is, and there are now four in all (see links below).

But Feta will always be close to my heart and I’m proud to say it was to become (and the sequels too) one of the very few books to be written in English about life in the economic crisis by a non-Greek living in the country during that time. It prompted Greek author Stella Pierides to suggest: “This book might become a future reference source about life in unspoilt Greece.”

It may have been a presentment of sorts and in 2021, I was thrilled to be contacted by a charming Greek girl called Panayiota, who told me that Feta and the following two memoirs had been offered on the syllabus of a literary course she attended in a northern Greek university, under the theme of how foreigner writers viewed Greek life during the crisis. She had written a paper on the subject. When I first started writing Feta in our Greek rural village during a cold winter, I wouldn’t have believed it would end up on a university syllabus. Or that Wallace may even have been the subject of some literary scrutiny. About time!

I’m grateful to all my blog readers on this site (some of you have been following my Greek blogs since the beginning) and others who have read my books and shared my stories and had a laugh over some of our more daring, crazy exploits and those of the famously crazy Wallace. I’m grateful to those who still write to me to offer their feedback. One Facebook friend recently told me she has read Feta 10 times so far. “Feta is my comfort-blanket read.” That’s a first! Many reviews and comments have been humorous. “More than Feta, this book is a whole picnic hamper of delights,” said one Amazon reviewer.

It would be true to say that going to Greece and writing the books changed our lives for ever, and only for the better. The only note of sadness in our otherwise happy life was that dear Wallace, one of the stars of Feta, passed away at the age of 16 in 2017 after we moved back to Britain. We were devastated, as Wallace had been through all our adventures with us and had been a talisman, as well as a welcome distraction at times. Few Greeks we lived amongst will ever forget his antics I’m sure, and neither will the many readers who wrote to me after Wallace died with kind thoughts and wishes.

The main consolation I have in Wallace’s passing is that he had a wonderful life and hopefully his memory will live on in my Greek books.

Feta extract

If you haven’t read Things Can Only Get Feta, here’s a funny extract from the book of one of our crazier exploits, when Jim and I set out to visit the archaeological site of Ancient Messene (10th century AD), north-west of Kalamata. The only problem was we had Wallace with us and, as we’d discovered on an earlier attempt on Messene, only guide dogs were allowed inside this large gated site, even on a near-deserted January day. While we sat in the car eating chicken sandwiches for lunch, we mulled over how we could blag our way inside with the dog. Jim finally came up with a daring strategy. Inspired by the once-warring Spartans who’d also dreamt up unlikely ways to sneak into Ancient Messene, Jim planned to get inside with Wallace hidden in his rucksack . . . . .

“Okay. But there’s one big problem: how do we get Wallace to stay quiet in the rucksack and not start barking?” I said.

Jim thought for a minute. “It sounds a bit gross but we’ll put him inside with the last chicken sandwich. Then we’ll zip the bag at the top and leave him a little air hole. He’ll be busy eating. You know what he’s like about chicken.”

Wallace always had a thing about chicken because Brigit, his kind but eccentric breeder in Edinburgh, fed all her puppies with roast chicken, which was a disaster for feeding programmes later. It explained why chicken was the only food that the fussy Wallace liked unequivocally. He was so besotted with chicken that we had broken every rule in the dog-rearing manual by using the word ‘chicken’ on occasions where danger loomed and every other command was flatly ignored. I turned and looked at Wallace on the back seat. He was panting. He’d definitely heard the ‘chicken’ word.

I expressed serious doubts about the plan but Jim was more optimistic.

“Don’t worry,” said Jim, soothingly, “He’ll be okay in the rucksack. Remember the time we carried him in it when we were hill walking in Scotland and he hurt his paw and was limping? He was good and quiet then.”

“What would the staff do if they caught us with Wallace?”

“Call the cops, put us in the cells for the night. Feed us two-month-old mizithra cheese and village bread.”

My teeth started to ping. “Ach, let’s go for it!”

If nothing else, at least we’d have a bit of a laugh. And in a cold January in Greece, you can get like that, wanting a laugh, any laugh.

“Let’s try him out in the rucksack first,” said Jim, unzipping it and taking things out. First, we threw in a couple of Wallace’s dog biscuits and lifted him inside the bag, which was roomy. He didn’t like it at first but when he caught a whiff of the biscuits, he squirmed around inside to retrieve them, thinking it was a new game, better than hiding biscuits in shoes.

I wasn’t totally convinced, but Jim still seemed confident, and I guessed it was just a bit of a boy thing.

“Okay,” he said. “Get ready to leave now. Get all your stuff. As soon as we unwrap the chicken sandwich and drop it in, we’ve only got a few minutes or so to get through the gate and on our way.” He checked his watch at the same time, as if this was a finely tuned military raid.

We got out of the car and locked it. Jim put on the rucksack with Wallace in it and I dropped in the chicken sandwich, torn into several pieces, which was the messiest part of the plan, and zipped up the bag, leaving the air hole. The minute the sandwich hit the bottom, Wallace was down there like a deep-sea diver and the bag was wriggling like mad, then all went quiet. I could almost hear his lip-smacking enjoyment over the chicken. We walked quickly through the main gate, Jim stood to one side while I went to the small cabin window. I remembered the attendant from the first time we came here, but assumed she wouldn’t recognise me after a summer of foreign visitors. I asked her what time the site closed.

“Are you together?” the woman said, pointing to Jim.

“Yes?”

She looked at him with narrowed eyes. “Can I ask what’s in the rucksack the man is carrying?”

“Just lunch things,” I said in a nervous, squeaky voice. I glanced at the rucksack and thought I saw the edge of it was wriggling. Maybe she saw it as well.

Jim sensed the hitch, aware that Wallace was growing restless, eager for another chicken soother, so he started walking down the dirt track that led between broken columns and the outlines of ancient buildings.

“My husband’s impatient…big archaeology fan. Been reading all about Ancient Mess…”

“Okay,” she said, cutting me off. “But you must be back by 3.30 when the site closes.”

I turned and legged it down the track, smiling to myself. When I caught up with Jim I could hear Wallace starting to whine and the zip was coming further apart at the top as he tried to get his snout into the cool air. Jim walked faster. The site sloped down to an old amphitheatre and from there it was a short walk to a cluster of olive trees. Once there we were safe, out of sight of the entrance cabin.”

. . . . . or were we? Find out how the smuggling strategy panned out finally, one of many amusing adventures in Things Can Only Get Feta

Book extract and all photos ©Marjory McGinn

To celebrate 10 years of Things Can Only Get Feta, the ebook will be discounted to 99p UK/US for three days on Amazon stores from Monday July 17. I hope enjoy it.

To buy Feta on Amazon UK or US click this link:

The book is available as an ebook and paperback on all Amazon sites. The other books in the best-selling Peloponnese series of memoirs, Homer’s Where The Heart Is; A Scorpion In The Lemon Tree, and A Donkey On The Catwalk, are also available on all Amazon sites, the paperbacks also through Barnes & Noble, Booktopia in Australia, and independent bookstores.

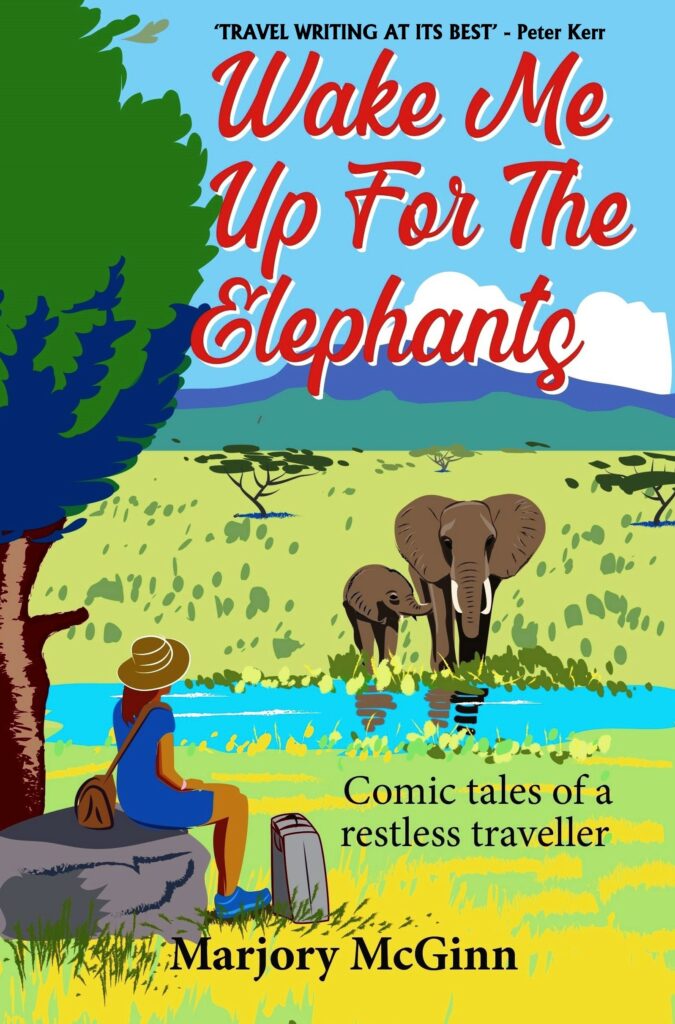

Marjory’s latest book Wake Me Up For The Elephants is a travel memoir with a broader canvas: Africa, Fiji, Australia, Scotland, Greece, Ireland. It’s a collection of candid and hilarious tales based on real journeys many taken by Marjory as a journalist and described by best-selling author, Peter Kerr, as “Travel writing at its best.” The book is in part a prequel to the Greek series of memoirs on what the author’s adventurous life was like even before she embarked on the Big Greek Odyssey.

The ebook and paperback are available on all Amazon sites. To buy the Kindle version, in either the UK or the US, click on one of the links below:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B0C2N788HD

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0C2N788HD

For all books by Marjory McGinn visit her Amazon page: https://www.amazon.com/author/marjory-mcginn

Or visit the website: https://www.bigfatgreekodyssey.com

If you have liked Marjory’s books, do consider putting a review on Amazon sites. It helps a book become more visible and is always appreciated by the author.

Thanks for stopping by.

© All rights reserved. All text and photographs copyright of the authors 2010-2023. No content/text or photographs may be copied from the blog without the prior written permission of the authors. This applies to all posts on the blog.