IT’S spooky, the rare times when reality imitates fiction. In my case, this was something of a huge revelation and it happened a few months after publishing my recent novel, A Saint For The Summer. It’s a contemporary story set in the Mani region of southern Greece but with a narrative thread going back to the Second World War in Kalamata. I spent four years in this region, from 2010, and I have written about my experiences there in my three travel memoirs (see website books page).

The new novel follows the story of Scottish journalist Bronte McKnight, who goes to Greece to help her expat father Angus solve a mystery from the war, when his father Kieran, serving in Greece with the Royal Army Service Corps, went missing in the Battle of Kalamata. This disastrous battle in 1941 has been called the ‘Greek Dunkirk’, when around 17,000 British and allied soldiers, retreating from the German advance in central Greece, ended up in Kalamata, the ‘end of the road’, awaiting evacuation to Crete. Around 8,000 were left stranded on the city’s beach at the head of the Messinian Gulf as British warships, under heavy German fire, were forced to retreat.

The novel follows the exciting but difficult path Angus and Bronte must take, with few leads, to find out what became of Kieran during the battle, and if he died in Greece, where he was buried. They are helped in their quest by a cast of memorable Greek characters.

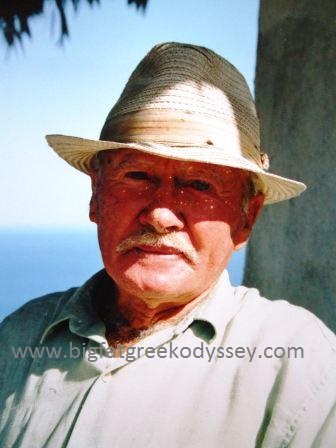

Readers have asked me what provided the inspiration for the war strand of Bronte, Angus and Kieran. I became curious about the Battle of Kalamata while living in this southern region, partly because it had a huge impact there, and yet beyond Greece, it was almost unknown. I began researching the topic while living there. The plot idea about Bronte and her missing grandfather pretty much dropped into my head during my stay in Greece. I did think though of my own father, John McGinn. He served in WW2 in the RAF Regiment, which was a specialist airfield defence corps and fighting force, formed in 1942. I knew he had been deployed to north Africa and Italy, and was in some horrific combat situations, but that’s all I knew.

I therefore didn’t base Saint on his war experience, and as far as I knew he hadn’t been sent to Greece, but I did base Kieran’s personality and his Celtic looks on my father, who had magnificent wavy auburn hair and fine bone structure. He was a handsome young man, full of high spirits, Scottish born, but also with Irish heritage.

Writing Saint had been a fairly intense experience, with quite a bit of research to undertake, so after it came out, I took a summer break from writing. Yet I couldn’t quite get the WW2 aspects of the story out of my mind. Curiously, it brought my thoughts back to my father again and made me speculate some more about his own war exploits. I knew so little. As a kid, I used to ask him for his war stories and he always flinched, saying he didn’t feel comfortable talking about it, and I accepted that it was something he preferred to forget.

As he died a long while ago, sadly, and was estranged from much of his family when we moved from Scotland to Australia in the 1960s, I had no way of finding out any more. A search online a few years ago for his war record had yielded nothing, as I didn’t have his squadron number for one thing. Or so I thought. I did have, however, a fine collection of old family photos and some of my father in the war (above), and a mass of memorabilia that had been in storage for some years. I promised myself I would sift through it properly once I took a break from travelling and writing books. It was now time to get started.

After sorting through some old documents, I came across two yellowing photocopies of censored Allied Forces postcards from my father to his family back in Scotland. The first carried Christmas greetings, sent from the Middle East in 1943, with a flourish of palm trees and minarets, with my father’s tiny, cramped handwriting across the top from “LAC (Leading Aircraftman) McGinn” to his family, wishing them a Merry Christmas. It also contained his squadron number and service number. I was thrilled with this. It was invaluable. The second Christmas postcard, dated 1944, was similar but showing just a map of the Mediterranean. With this information, I went online to see if I could find out anything about the exploits of this squadron. Fortunately, there is now a lot more war information online than in previous years and the amount of material uploaded (eyewitness accounts, journals) from the two world wars grows continually.

It was online that I had a breakthrough. And oddly enough, it was this factor of being able now to search for vital war information on the internet that had been a pivotal part of Saint when the fictional father Angus tracks down a possible pointer to the disappeared Kieran on an online veterans’ site. The reason for this inclusion in the plot was because in Greece I had come across several expats researching the Battle of Kalamata and lost relatives, who had done something similar, and it had impressed me. So, in effect, I was, without really meaning to, following my own fictional plot.

On a couple of sites I found accounts of the exploits of my father’s 2771 squadron, particularly in Italy in 1944, and some of the information was attributed to a book published in 2013, which I immediately purchased and for which I am eternally grateful (RAF Regiment at War 1942 to 46 by Kingsley Oliver). I was able to establish for the first time exactly what my father had done in Italy, which gave me huge reverence for his war experience and explained why he hadn’t wanted to talk about it.

Not only that, I had the amazing good fortune of finding photos online (and some are also in Oliver’s book), which I had never seen before of the squadron during the battle of Monte Cassino. I recognised my father straight away in one of the pictures of the squadron in a ravine near Cassino, bombarding enemy positions (above). He was manning a mortar gun, looking impossibly young. And in another, he is standing in the allied ‘headquarters’, an archway under the Colle Belvedere aquaduct north of Cassino. Firm proof of where he had been during the Italian campaign. And there was another surprise too at the end of my research that I was wasn’t expecting. More of that later.

The squadron had initially been deployed to north Africa and after the surrender there of the Axis powers in 1943, the squadron were sent into the Italian Campaign against the occupying German forces. They went first to Naples and Rimini, and in the spring of 1944 to the front line, not far from Monte Cassino. The Battle of Monte Cassino was four massive assaults by the allies on this strategic part of the German-held ‘Gustav Line’ that crossed the rugged terrain of central Italy, with the aim of forcing the Germans to retreat, and to protect the route to Rome. Much of the fighting centred on the steep hill at Cassino, crowned by a vast and ancient Benedictine monastery which the Germans were using as an observation post, though firing from obscured positions on the steep sides of the hill.

The allied efforts to trounce the Germans in Cassino were amongst the fiercest and bloodiest engagements of the war in Western Europe, involving French and American troops and several British regiments, along with its allies: Indians, New Zealanders, Poles. Because of the intractable terrain, cut by rivers and deep ravines, the British troops dubbed the area ‘The Inferno’. The battles here were comparable to some of the worst scenes of WW1, with 55,000 allied casualties. And under heavy aerial bombardments, particularly from the American forces, the old monastery was reduced to rubble.

The RAF Regiment was there in a strategic fighting role alongside other British regiments. One of the other aircraftmen in the 2771 squadron, who would have fought alongside my father, Corporal Alf Blackett, later wrote of his wartime experiences in Cassino and the relentless fighting. “It’s a grim life, clinging tenaciously to the side of a steep hill with the Germans in strength on the other side and the RAF regiment men holding a sector of the front line.” At one point during an assault he said: “The regiment moved up to their positions on a moonless night in their tin hats and khaki. Near to the front, the officer told them to smoke their last cigarette. ‘This, chaps, is going to be one mad ride’.”

One eyewitness described it as a “living hell”, with the wounded and dead ferried down the hill in a vehicle called the Death Wagon. Although the allied forces were finally victorious in driving the Germans away from the Gustav Line in this decisive battle for Italy, I did begin to understand at least why my father had never had the stomach to talk about Monte Cassino. And while he wasn’t killed, like the fictional Kieran, or badly wounded, he came out of the ferocious bombardments having lost much of his hearing, a disability that affected him for the rest of his life.

But the greatest surprise to me from my research into the operations of 2771 squadron was that after the Cassino engagement ended in May ’44, the squadron was deployed to Greece in the autumn, after the German withdrawal from the country. Some British forces, including the RAF Regiment, were there to support the Greek government troops, fighting the Communist Party (EAM), at the start of the Greek Civil War. The 2771 squadron defended the Hassani airfield, south-east Athens, and were also tasked with supporting British ground forces in central Athens against communist attacks. My father, as far as I remember, had never mentioned his time in Greece, but I calculated that the second postcard I found would have been sent by him from Greece, Christmas ’44. By the spring of the following year he had been redeployed to Yugoslavia.

The fact my father had been to Greece at all was a huge revelation to me. From a personal point of view, Greece has always been a driving force in my life from my childhood – and fate definitely had a hand in it. As a newly arrived Scottish migrant to Australia in the 1960s, at my Sydney school, I was put under the wing of another ‘migrant’, a young Greek girl called Anna. We spent many long summers together and in time I became almost part of her extended family. After leaving school, I had gone to Athens to work for a year and have visited Greece numerous times, culminating in my recent four-year stint. In all that time, I had no idea that my father’s war postings had taken him there.

For me to have written a novel with a Scottish soldier lost in the Battle of Kalamata in Greece, whom I decided to create in my father’s likeness, seems incredible to me now, as if the strands of our lives had become woven together at strategic points and fate had lured us to the same location, although I, at least, never knew until now.

When I see old photos of my father, after signing up to the RAF Regiment, it tugs at my heart to see how boyish and full of enthusiasm he was. Aged 18, and a gallus young lad (daring, high spirited), it would have seemed in the beginning like a grand adventure into the unknown, something I could relate to when I went on my own youthful journey to Greece.

My father was born in a rundown tenement in the infamous east end of Glasgow and the war was, for him, as for many working-class kids – the great escape. That much at least he told me when I was a curious youngster. “It was an escape from poverty,” I remember him telling me. Yet it turned into a descent into the Inferno in Italy. At least he survived.

Had I not written my first novel with its WW2 strand, it’s quite possible I may not have felt inspired enough to dig further into my father’s war record. I’m certainly glad I did and the fact that my book and his life are somehow now intertwined on some level has touched me greatly.

With the 100th anniversary of the RAF this year, it’s pertinent to remember all those who fought so valiantly in it, including the great RAF Regiment. We salute you all. And I dedicate this post also to the late, and much loved, John McGinn.

- If any readers have relatives who were in the RAF Regiment’s 2771 squadron and who have more information about their operations or who may just want to get in touch, please do. You can email the website info@bigfatgreekodyssey.com

Information and photographs of the RAF Regiment’s war history can be found at the RAF Regiment Heritage Centre www.rafregimentheritagecentre.org.uk

A Saint For The Summer is available on all Amazon sites and through independent book stores, quoting the ISBN number: 978-1-9999957-1-3 If you like the book and if it resonates with you, please do get in touch. I love to receive messages and feedback from readers, and Amazon reviews are also very welcome, too.

Here’s a universal link: https://bookgoodies.com/a/B07B4K34TV

Comments on the blog are very welcome. Thanks for calling by.

© All rights reserved. All text and photographs copyright of the authors 2010-2020. No content/text or photographs may be copied from the blog without the prior written permission of the authors. This applies to all posts on the blog.