WHEN we decided 10 years ago to leave Scotland and have a year’s odyssey in Greece at the start of its economic crisis, people said this was madness. Yet now, with the Corona virus causing misery around the world with ‘lockdown’ restrictions on lifestyle and travel, we would have been madder still not to have gone for the odyssey while we had the chance.

As we look back to that spring of 2010, when my husband Jim and I and our fizzy Jack Russell terrier Wallace set off, we know that despite the economic risks, it turned out to be one of the best decisions we’ve ever made. And as one year stretched to four, it changed our lives completely.

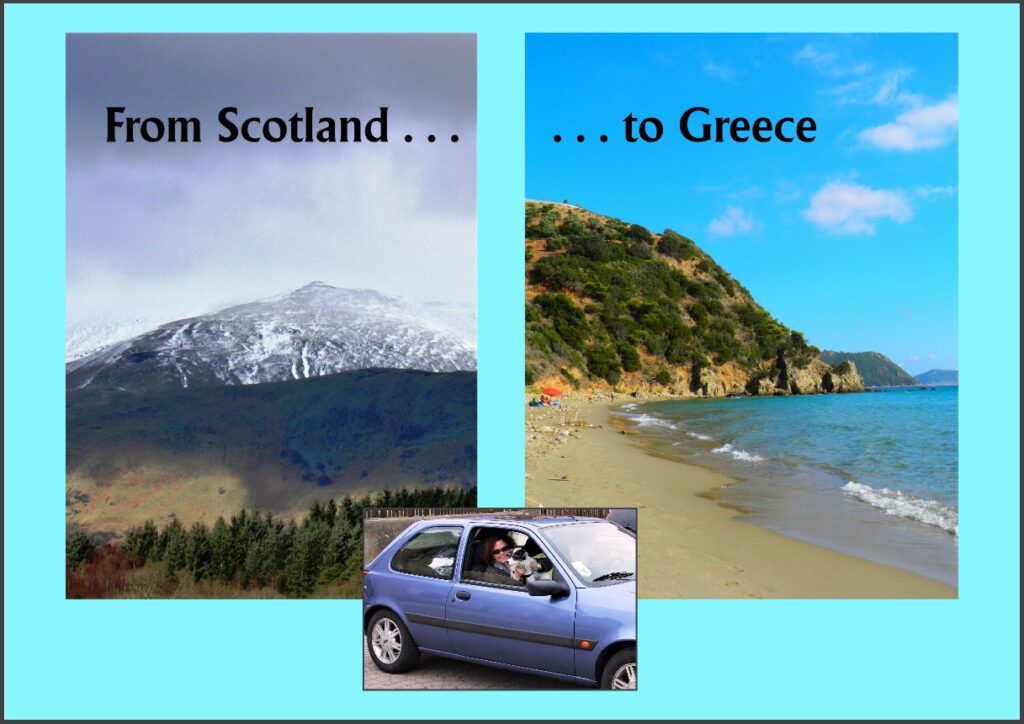

We left with Britain during a harsh recession and our village in central Scotland, near Stirling, during a blast of Arctic weather. We had the added uncertainty of leaving regular employment in Scottish journalism to cast ourselves adrift with modest savings, but with the hope of future freelancing. But Greece, despite its massive bailout from the EU and ensuing austerity measures, still seemed like a safer option, to our way of thinking anyway.

Even now, I recall vividly the excitement of planning the trip which was no small undertaking. Months beforehand we had a bullet list of things to do filling four A4 pages: renting out our Scottish apartment and putting personal items in storage; all the endless bureaucracy involved in cutting loose from Britain; having to limit our travel luggage to what would fit in a small Ford Fiesta. Amazingly, everything in the picture above was shoehorned in finally on a grey dreich Scottish morning, threatening rain.

And because we were taking our much loved terrier with us, there was a long list of necessities for him as well: microchip, pet passport, vaccinations. And hotels had to be booked along the way that were pet friendly, no easy task back then. While Wallace had a fabulous personality and was hugely entertaining, he did have the crazy Jack Russell gene: boisterous and often unpredictable. So it ramped up the uncertainty as well. A comical Scottish friend commented: “You’re not taking Wallace to Greece? Haven’t they got enough problems there already?” Indeed they did!

We drove south to Dover and took the car ferry to Calais and then made our way through France, Switzerland and Italy, to Ancona, for the crossing to Patras in Greece with a pet-friendly cabin. It was a great trip and Wallace was fine most of the time, apart from barking at every motorway toll booth attendant and having one or two angsty moments in hotels, the most memorable being in Italy. While we waited at the front desk in a large hotel in central Italy, Wallace took a dislike to two rowdy teenagers skittering about the foyer and launched into his characteristic slightly hysterical bark. The manager checking us in had a massive strop, which set Wallace off again. We were forbidden from leaving him in the room alone while we went out to dinner, so we had to take him with us. But that’s another nervy story.

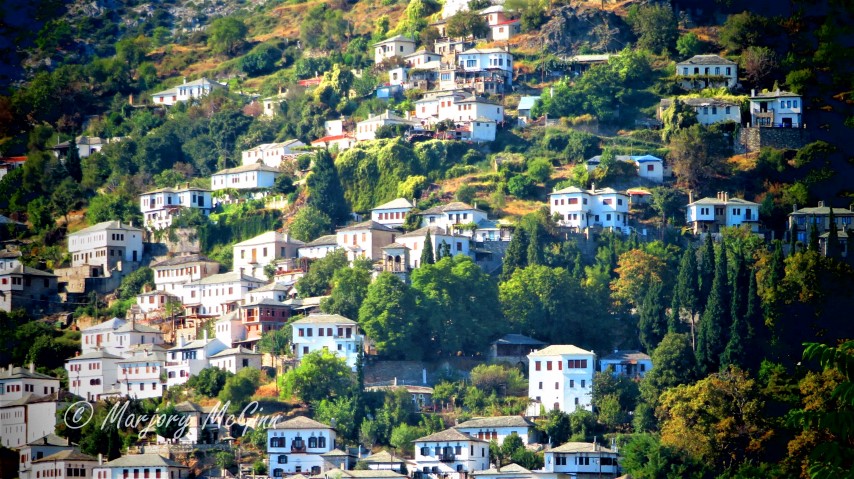

Once we’d arrived in Greece, staying in a 4-week holiday let, and had our first taverna meal and swum in a warm sea, everything clicked into place. I’ve travelled to Greece many times during my life and worked in Athens in the 1970s for a year, and in those first few weeks in 2010, I couldn’t detect any sense of angst in the country. Life seemed sweet in the southern mainland least. It was a warm April, people seemed happy, tavernas and cafes had brisk trade. What we didn’t know then was that Greece was right on a tipping point, still with a lot of the ‘siga siga’ laid-back quality we all love about the country. But that was about to swing over as 2010 progressed, with unimaginable changes and hardships on the cards for Greek people.

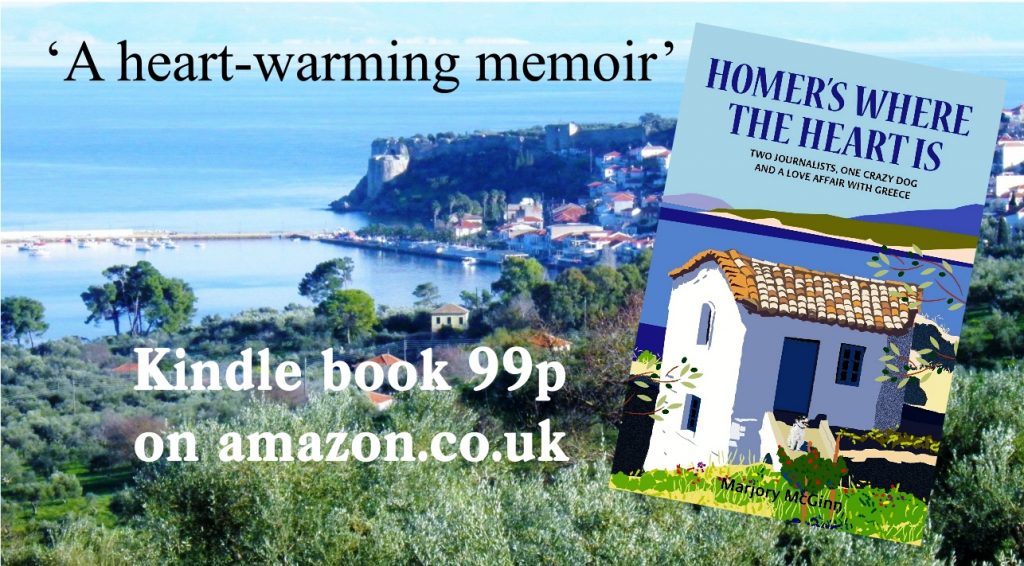

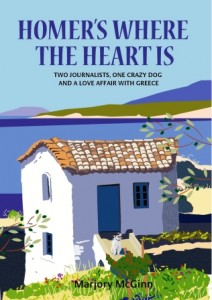

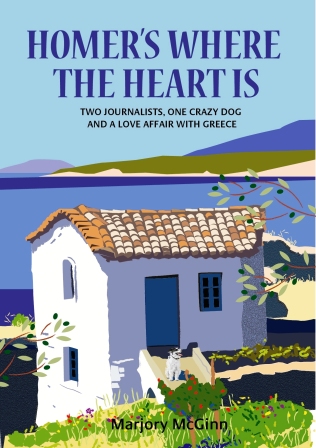

We had decided to live in the Mani peninsula of the southern Peloponnese, a wild and authentic region. We rented a small stone house in the hillside village of Megali Mantineia, just south of the city of Kalamata. We stayed in the village a year, which became the basis of my first Greek memoir, Things Can Only Get Feta (2013) and which I’ve written about in various publications as well as on this blog. The rest of our adventures in other locations in southern Greece are recounted in the sequels, Homer’s Where The Heart Is and A Scorpion In The Lemon Tree.

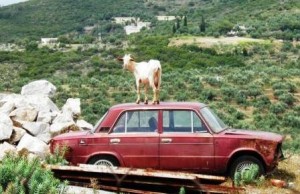

In our four years in Greece, we managed to cram a great deal into our lives out of sheer delight at being able to have a mid-life adventure at all, in those crisis-ridden days. We travelled regularly around the three peninsulas of this region and to the north Peloponnese and saw most of famed sites like Olympia, Mystras, Arcadian villages, and the island of Kythera. Occasionally there was some difficulty, travelling with a dog, in a country that regarded them more as working animals, like the day we had to smuggle Wallace into the Ancient Messene archaeological site because dogs were banned. Because of Wallace, there were mishaps galore (mostly comical). Yet conversely, some of the decisions we made just to accommodate Wallace on our trip, ironically turned out to be wise decisions which I describe in my memoirs.

We had a huge challenge on the gorgeous World Heritage Byzantine rock island of Monemvasia, on the east of the Peloponnese, when Wallace got the jitters in the historic 12th century house we rented for a few days. Situated in the heart of the fortified settlement, where the owner told us some devilish times had been suffered by the householders during an Ottoman-Turkish siege, Wallace seemed to picked up grisly vibes. It was all brought to a head in a storm, when he howled like a banshee and then accidentally wrecked a piece of ancestral furnishing. If you’ve read my first memoir, you’ll know what I refer to.

In all, throughout our odyssey, we made a point of not sinking into the familiarity of expat communities, entertaining though they were, but sought out a more authentic Greek life. We went out of our way to meet neighbouring rural Greeks for which I had to brush up fast on my rusty Greek language skills. We went to festivals, endless church services, at least one funeral but no weddings, olive harvests, coffee mornings in hornet-infested, ramshackle farmyards, and dubious cheese tasting events.

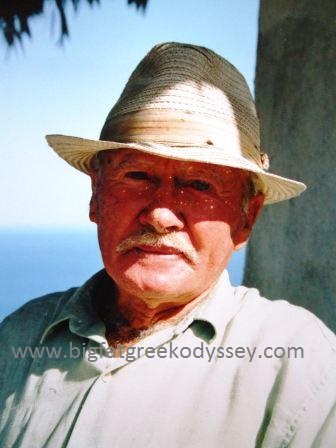

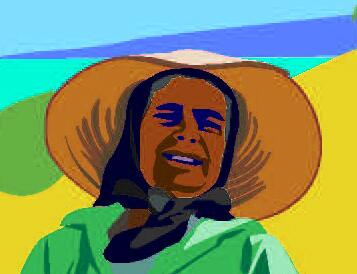

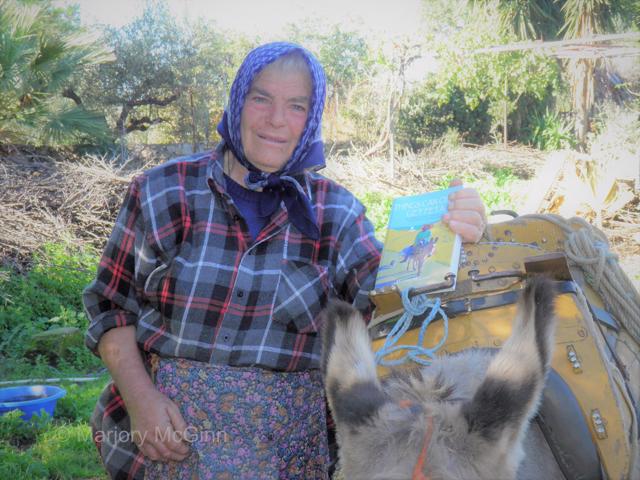

This turned out to be another good decision. It is the friendships and the kindness of Greek people even in dire circumstances that will stay in my memory forever; people like Foteini the goat farmer, who turned out to be an unlikely literary muse for me and who appears in all three memoirs.

A tough Maniot farmer and a charming but eccentric woman, she became a friend and provided me with many hilarious encounters that seemed skewed from other eras of old Greece. I well remember us sitting in her dilapidated village house one winter in front of a roaring fire while wind whistled through the cracks in her kitchen walls. We drank Coca-Cola and roasted chunks of goat cheese (which we hated, sadly, but pretended otherwise) on skewers over the flames. Other times we also observed and smiled over her many comical rituals: peeling bananas at a sink and then washing the fruit, or indulging in riskier pursuits like almost blowing up her farming shed while making Greek coffee.

But these were also challenging years. While Jim and I were freelancing for overseas publications and were able to live frugally without being affected directly by the crisis, we had involved ourselves in Greek communities and witnessed the impact of the crisis on locals. This was particularly so in 2012, when social unrest and poverty began to climb and Greeks became uncharacteristically depressed and nervous. It was the first time we questioned whether we had any right to continue our Greek odyssey.

I have visited Greece during other difficult times in its history and these crisis years were no less frightening, especially with the rise of a particular extreme and violent right-wing party that had gained seats in the Greek parliament. I even began to hear Greeks anticipate the sight of tanks rumbling down the streets again, as they had during the infamous military dictatorship of the 1960s and 70s. Fortunately it never came to that. In the end, in 2015, we did finally leave but only because an illness in Jim’s family had made a return to the UK the right thing to do at that time.

Although we’ve only been able to return to Greece for long holidays since 2015 and not an extended return, our former odyssey lives vividly in our minds and sustains us in so many ways. It is never forgotten, is always a source of lively discussion between Jim and me and has inspired us during happy and sad times, including August 2017, when dear Wallace passed away in England, aged 16 years. We could rightly say that he’d had an amazing life, and an odyssey that few dogs ever get a crack at, and which he took to with verve and stoicism especially during a serious illness that I touched on in Homer’s Where The Heart Is. And few of the Greeks we came in contact with will ever forget some of Wallace’s more diverting antics.

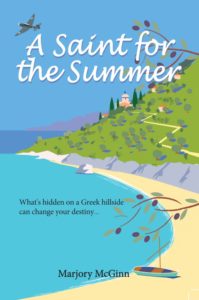

The Greek ‘journey’ for me still continues because after finishing my three memoirs, I wrote two novels in a series (A Saint For The Summer, and recently, How Greek Is Your Love?) both set in the Mani region, and more may be planned. And especially in these worrying times in lockdown, due to the Corona virus, Jim and I find ourselves thinking more and more of those Greek years, grateful we were able to have an amazing, long adventure that neither of us had anticipated in that freezing winter when we left Scotland.

If I’ve learnt nothing else from the Greek odyssey it’s been that when the opportunity to (safely) change your life comes your way, take it and don’t let fear cloud your vision. And at the very least, don’t worry over the awkward, nagging details, because “you never know what the next sunrise will bring you”, to quote a Greek saying. That applies more now than ever before as our world turns upside down with health worries. And let’s pray the ‘new normal’ will one day allow a few restless souls to still cut loose on foreign shores for their own big, fat odyssey.

* All Marjory’s books are available from Amazon stores worldwide, Barnes & Noble, and in Greece can be ordered through the Public stores, www.public.gr or ordered anywhere through independent bookstores.

The Peloponnese series of memoirs:

Bronte In Greece series of novels:

For more information about Marjory’s books, please visit her Amazon page or the Greek books page on our website www.bigfatgreekodyssey.com

If you like the books, please consider putting a small review/comment on Amazon. It all helps to raise the profile of a book. And is always welcome. Thank you.

Thanks for dropping by. All comments are gratefully received. Just click on the ‘chat’ bubble at the top of this page.

© All rights reserved. All text and photographs copyright of the authors 2010-2020. No content/text or photographs may be copied from the blog without the prior written permission of the authors. This applies to all posts on the blog.