“YOU can’t have moussaka for Christmas,” said one of our English expat friends in the Mani just before our second Christmas in the region, as we discussed festive menus.

“Why not? It seems perfectly reasonable for a Greek odyssey.”

“Okay,” he said with a shrug. “But you can get moussaka any time. Christmas calls for turkey, or at least a chicken. It’s tradition.”

Yes it was, but not necessarily here. Of course he thought we were mad opting for moussaka, but madder still was the whole British faff of trying to replicate Christmas in Greece, with turkeys and even Brussels sprouts. One genial expat who lived full-time in the Mani had bemoaned the fact he had not been able to grow a sprout yet in his garden. If there was one thing I didn’t miss about a British Christmas it was the metallic after-taste of a sprout.

It seemed bizarre to even think of a normal Christmas when some years you can swim until the end of the year ̶ in the southern Peloponnese at least. And if had been any hotter that particular December we may have plumped for a day at the beach, like some of my teenage Bondi Beach Christmases, when I was growing up in Sydney.

That was because the traditional Christmas in Australia is bizarre as well. I had plenty of those in my childhood from my Scottish family keen to stick to the rules of the ‘homeland’, with turkey or a fat chook (chicken) in 100-degree heat, watching the tree ignite from overheated festive lights, and all the oldies squabbling and then passing out in front of British Christmas reruns on the TV.

Christmas in Greece is refreshingly and sensibly low-key, no hysterics, no burn-out. It’s more about family, a time of reflection and religious observation. Greeks do buy presents but they are exchanged mainly on New Year’s Day, which is the feast day of Ayios Vassilis, the Greek version of Santa Claus, without the red suit and reindeer mates.

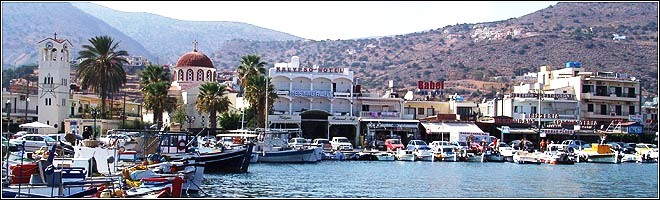

Villages still opt for the old tradition of a decorated boat like this one in the square at Koroni, Messinia

Some younger Greeks, particularly in towns, have slowly adopted elements of the western Christmas, and having a decorated tree is something of a status symbol now, despite the economic crisis. However, the old ways remain, especially in villages. You still see illuminated boats in a village plateia because this symbol is associated with Ayios Nikolaos, whose feast day is earlier in December, and he’s the patron saint of sailors. You will also hear kids shuffling about the streets on Christmas Eve singing the kalanda song, a kind of Greek carol which might earn them a coin or a sweet.

Our first Christmas in the Mani had been in 2010, the year we moved into the hillside village of Megali Mantineia. On Christmas Day there was a morning service, which was hard to ignore as the sound of the chanting rolled out over the entire village. After this, there were quiet preparations for the long family lunch.

In the morning some village friends had brought us gifts of olive oil and kourabiedes (shortbread) with a thick dusting of powdered sugar. We had visited our farming friend Foteini in the morning and took her a small gift. She was having her Christmas lunch with a neighbour Eftihia and her family but, as with most rural Greeks it would be a modest meal, probably roast goat, since everyone here kept goats.

Foteini insisted we come with her to Christmas lunch and it was tempting but we had already accepted lunch with an expat friend further down the Mani. She had recently retired to Greece and perhaps it was an attempt to summon up the familiar, but it was a proper British meal with all the trimmings and plenty of wine. It, too, seemed bizarre and slightly out of place, but at least we could work off the lipid overload by pacing round the nearby olive groves after lunch.

During the second Christmas we were living down the hill from Megali Mantineia in the seaside village of Paleohora. We were renting a house from a genial Greek couple, Andreas and Marina. On Christmas Day, while they stayed at their home in Kalamata for a family gathering, we planned to have a quiet lunch this time, and make the moussaka, for which we had bought all the ingredients. But it was such a gloriously sunny day, despite being cool, that even after all the fuss we had made about the moussaka, we changed our minds.

We drove instead up to Megali Mantineia to have lunch in one of our favourite tavernas, the Iliovasilema (Sunset taverna). The place was open though the whole family was gathered at one long table to eat their lunch of succulent oven-roasted goat and lemony potatoes. There were several other people dining, a few expats and Greek couple from Athens with a house in the village, but somehow we were all annexed to the family proceedings and it turned out to be one of our loveliest Christmases: traditional, with plenty of parea (company) and no fuss.

During our second Christmas in Paleohora, however, we did discover one surprising thing about our landlord Marina. She had a secret obsession for some of the rituals of Christmas and it all started way ahead of the festive season. It became one of the chapters in my sequel Homer’s Where The Heart Is, which, to end my Christmas blog, I would like to share in a small excerpt:

“One Saturday there was a knock at the front door. It was Marina and Andreas. Marina was loaded up with things in baskets and myriad plastic bags hooked over her wrist. I was very afraid though when I saw the big pointed red hat of what appeared to be a papier maché Santa Claus.

“Good morning, I’ve brought some Christmas things. I will just sort them out, yes?” she said.

With her usual proprietorial charm that we had fully accepted now, she barged passed us. I assumed she was taking them to the apothiki (store room) to leave until Christmas. Andreas stayed on the doorstep because his feet were muddy and handed us a bag of sweet oranges from his trees. We stood outside, talking and leaning on the wrought-iron railing on the top steps.

While we chatted outside we forgot all about Marina. Suddenly I became aware of furious scurrying and hammering going on behind us.

“What’s happening inside, Andreas?”

He rolled his eyes. “Marina has just decorated your place for Christmas.”

“What?”

We turned around and the living room, which had looked atmospheric and Greek, now resembled Santa’s Grotto at a John Lewis store. The big red Santa was on the dining table and tinsel was strung up over the fireplace, with Christmas lights, candle stands and a dozen statues of Santa Claus striking various festive poses.

“Here,” said Marina, pushing two festive woollen socks towards me. “For Christmas Day.”

“But Marina, it’s only November. Too early for Christmas, surely?” I pleaded.

Andreas shook his head. “I agree, Margarita, but Marina loves Christmas, you have no idea.”

Oh yes I did! The living room − lit up and pulsating, lacking only a sound system for Christmas carols − told me so.

“This old place looks better now, don’t you think?” said Marina, hands on hips like the presenter of a TV home makeover show.

One of the things we liked about being in Greece at Christmas was the lack of commercialism and houses lit up like Blackpool seafront. It was a quiet, reflective time instead. But now we had the whole Christmas fizz inside the house. We laughed over it all later and slowly began to dismantle the effects, leaving some of Marina’s festive tat in place and hiding the rest in the apothiki, hoping she wouldn’t notice….”

Well that’s it for the year. To all readers, I would like to thank you for your continuing interest and support of the blog and my Greek books. I wish you a very happy Christmas and a prosperous New Year. If you happen to find yourself in Greece at Christmas, go for the roast goat every time, or have an Aussie beach Christmas instead.

(Text: © Marjory McGinn)

See you all next year.

Χρονια Πολλα. X

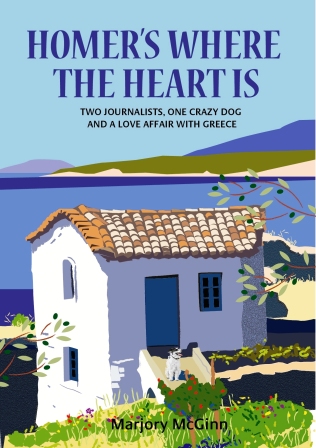

Homer’s Where The Heart Is

TO read more about living in Greece during the crisis in the southern Peloponnese, read my second travel memoir Homer’s Where The Heart Is.

This book is the sequel to the first, Things Can Only Get Feta (published in 2013) about the start of our long odyssey in the rural Mani.

To those who have already read the latest book, thanks for your kind comments and Amazon reviews, which are always appreciated.

Both books are available on all Amazon’s international sites and also on the Book Depository www.bookdepository.com (with free overseas postage).

On the website www.bigfatgreekodyssey.com you will also find a ‘books’ page with other information about the books.

To buy either of my books please click on the Amazon links below:

You can also find me on Twitter @fatgreekodyssey

And Facebook www.facebook.com/ThingsCanOnlyGetFeta

www.facebook.com/HomersWhereTheHeartIs

Thanks for calling by.

© All rights reserved. All text and photographs copyright of the authors 2015. No content/text or photographs may be copied from the blog without the prior written permission of the authors. This applies to all posts on the blog