AS someone who has been going to Greece all my life, since the 1970s, the political events of the past few months have saddened me. I am wondering, along with everyone else, how Greece’s economic situation and its politics ever got so convoluted.

In recent months the scenario has included punishing negotiations for a new bailout; a referendum called by PM Alexis Tsipras, who then ignored the results, as well as the 65 per cent of Greeks opposing austerity; a new and terrifying agreement signed with the Troika; a mutiny by some Syriza MPs; Tsipras’s resignation; a September election tipped; a new breakaway leftist party. There have been frenetic political twists and turns, like a manic rollercoaster with brake failure. Most Greeks claim to be confused now.

As one of my Twitter followers, a Greek teacher, recently said: “I don’t know which way is up or down any more? Worse, I don’t know which way is right or left.”

Many others are devastated. A female friend in Athens, with a young son, wrote to me recently, saying: “We feel that we are on a boat that’s sinking. We don’t know what comes next and we are trying to live from day to day.”

She also believes, as someone who works as an economist in the city, that the country will change drastically in the coming years after the next bout of austerity and the fire sale of assets.

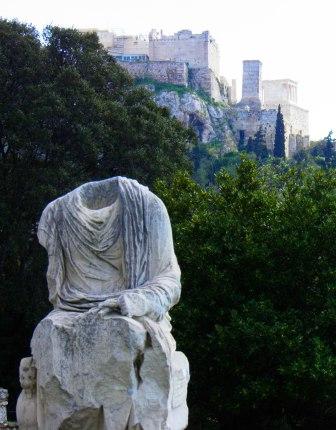

I too have had a feeling of dread for months that we are witnessing the last carefree days of the Greece that we all used to know and love. I hope my Athens friend is wrong, but in my heart I fear she is right. Change is coming!

A headless statue in the Agora, Athens seems to say more about the troubled present day city that it does about the past

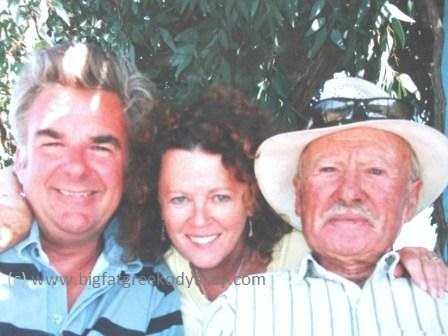

I have been in love with Greece all my life, from the early 1970s on my first trip, not long after high school in Australia, when I arrived in Athens for a short break and ended up staying for a year’s working holiday. Despite the fact Greece was then ruled by a military dictatorship, and it was yet another tragic time in its history, in other ways it was, culturally and socially at least, a time of simplicity, even innocence, compared to now.

All the elements of Greek life and culture that philhellenes still love were there in abundance. I wrote about this time in Athens as a parallel narrative in my book Homer’s Where The Heart Is. When I first arrived in the city and stepped off the overland bus from London it was love at first sight: “It was nothing I could easily define, but more a fusion of disparate things, all maddeningly exotic to my young mind: the incomprehensible street signs, the old people dressed in black, the coffee shops, the bakeries wafting aromas of freshly baked bread and tiropites, and all the other smells even the bad ones – fetid drains and a city still staggering after a long summer heatwave. It all blended into a heady Levantine cocktail.”

I have had many trips to Greece since, some for just a few weeks’ vacation, but many were quite long, from a few months to my recent four-year odyssey in southern Greece.

When I remember the earlier trips, I feel so much nostalgia for that old Greece, whether it was in Athens or places of unique beauty like Santorini, or small unspoilt islands like Serifos, Sifnos, Paxos, Patmos and for a way of life that was simple and charming, where donkeys were more common than cars and you could only buy your yoghurt in ceramic bowls, where there was only one kind of coffee, Nescafe, and where the drachma still reigned. Joining the Eurozone was a futuristic folly. Despite not having much money, most people seemed happier, and were fantastically hospitable.

In 1989, I took a sabbatical from my newspaper job in Sydney and went to Crete for two months. It was totally unplanned, no itinerary, no rooms booked in advance. I took a boat from Piraeus to Irakleion and travelled to the Venetian town of Hania. I hadn’t planned getting sick either, but a stomach bug left me stranded in a harbourside hotel for days, where a doctor had to be summoned.

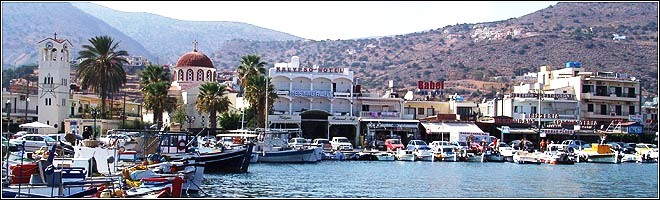

The harbour at Elounda in Crete, some years after Marjory’s first trip. Picture courtesy of www.dilos.com

Later on, a chance recommendation from a fellow Aussie made me seek out a convalescence of sorts in Elounda, a small undeveloped fishing village then on the north-eastern coast of the island. Too weak to bother with buses, I got in a taxi and asked the driver to take me to Elounda. It didn’t seem strange to the driver that when we got there, I hadn’t anything booked. Don’t worry, he said kindly, we’ll find you something. It was October after all and not bursting with tourists, not back then anyway.

Near the harbour he stopped the car, but before he started scouting for rooms, a small rotund woman rushed out of her house, towards the taxi. Did I want a room, she asked me.

The taxi driver waited patiently while I followed her inside to see the small apartment (a bedroom, bathroom and tiny kitchen) on the ground floor. It was simple and clean. I took it on the spot, the taxi driver was dispatched, happy with his healthy fare and tip. That was the start of a wonderful stay in Elounda, and a friendship with the couple upstairs, Poppy and George, with whom I practically lived for the rest of my stay, watching their TV, sharing meals, helping Poppy to prepare some of them. I would often sit on her upstairs balcony with a few neighbouring women, chattering and cleaning mountains of horta (greens) just collected from the hills.

The couple also took me out on their small boat, the Peristeri, for local excursions. Once they took me fishing at 5am to the nearby island of Spinalonga, before Victoria Hislop had been inspired to set her book The Island there, about the former leper colony. When I went it was just a rather ruined and forlorn outpost.

The rest of the time in Elounda, I rambled the hills behind the village, often with Poppy, often alone, and everywhere I went people invited me in for drinks, coffee, meals, parea, company. When I finally left, Poppy and George hugged me and told me I must stay in touch as if I were a long-lost relative.

Greeks were like that then. And they still are in many parts of the country, especially in the islands and rural places like the southern Peloponnese, where we spent four years from 2010, living the first year in a remote hillside village in the Mani and later in Koroni, at the tip of the Messinian peninsula. In these areas we were shown the same warmth and familiarity by locals, as Poppy and George.

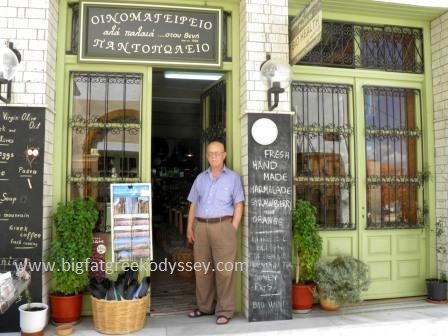

An old traditional shop in Koroni, a pantopoleio, on Karapavlou St, selling everything from wine to organic food and owned by the charming Tasos Sipsas

But Greece as a country has been slowly changing, of course. How could it not? It’s not a folk museum, after all. It has become more modern, European, apart from the plumbing, which remains antique! And inevitably, many of the old cultural elements are changing or disappearing. Fewer rural Greeks wear traditional clothing now. There are fewer kafeneia and ouzeries in villages than there used to be; there are fewer working villages. In the Mani we found that many wonderful hillside villages that were once full of life, shops and schools, were now inhabited by only a dozen or so locals. In many it was hard to find even one kafeneio or local store.

With the drastic economic changes and cuts that are coming, will too much of Greece’s traditional life and customs change irrevocably, to squeeze Greece into a rule-bound northern Europe template? Trouncing all the features that, ironically, tourists go to Greece to experience?

I think that’s something that everyone with any ounce of love for Greece should fight against. We must save the spirit of old Greece, its personality, its old customs and crafts, and its ideals of friendship and hospitality because, as so many other countries have found, once you dismantle a country’s soul and the uniqueness of its past, you can never really get it back again. No-one who has travelled to Greece from the 1960s onwards could come to terms with that loss. Not least the inimitable Greeks themselves.

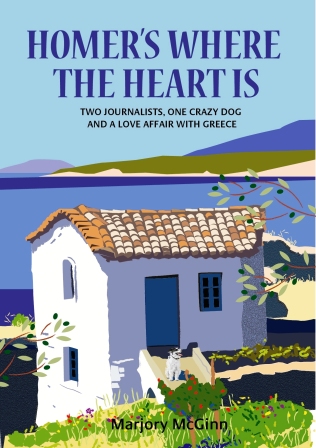

Homer’s Where The Heart Is

TO read more about living in Greece during the crisis in the southern Peloponnese, read my new travel memoir Homer’s Where The Heart Is. This is the sequel to the first, Things Can Only Get Feta (first published in 2013) about the start of our long odyssey in the rural Mani.

To those who have already read the latest book, thanks for your kind comments and Amazon reviews, which are always appreciated.

Both books are available on all Amazon’s international sites and also on the Book Depository www.bookdepository.com (with free overseas postage). If you are in Greece you can inquire about having the book ordered at your branch of the Public store www.public.gr

If any readers have queries about availability for both books, please contact me via the contact page on our website www.bigfatgreekodyssey.com where you will also find a ‘books’ page with other information about the books.

To buy either of my books please click on the Amazon links below:

You can also find me on Twitter @fatgreekodyssey

And Facebook www.facebook.com/ThingsCanOnlyGetFeta

www.facebook.com/HomersWhereTheHeartIs

Thanks for calling by.

© All rights reserved. All text and photographs copyright of the authors 2015. No content/text or photographs may be copied from the blog without the prior written permission of the authors. This applies to all posts on the blog.