Back in 2000, when I was living in Scotland and working as a freelance feature writer, I wrote a piece for The Sunday Times about actor Donald Sutherland, mostly about his early years working in repertory at Perth Theatre, which was fascinating. It was a phone interview and the actor was very charming and kind, and even included my mother Mary in the conversation, as you will see below.

He gave me a personal email address to contact him if I had any more questions, and I did some time later, though it had nothing to do with the original feature. However, it inspired a series of emails between us, sometimes touching, sometimes bizarre, and when it ended I kept all the emails. When I heard he’d sadly passed away in June 2024, I re-read those emails again and felt privileged to have had this unusual connection with him over four years.

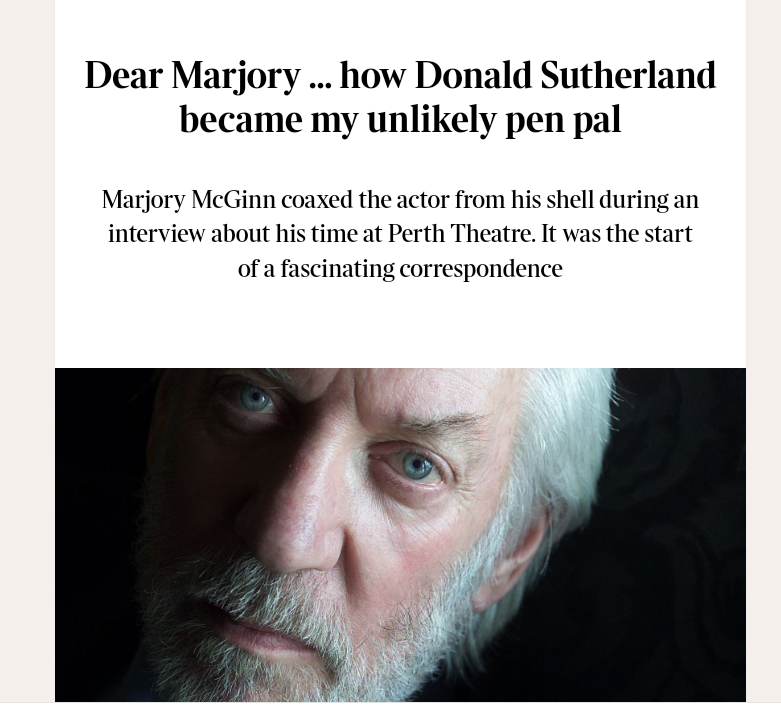

I felt it was a good time, the week he died, to write a small feature about our correspondence as my own small tribute to this Hollywood legend, and The Scottish Sunday Times published it. It had the internet edition’s social media pointer (see above), which was also delightful.

The feature included a picture of myself and my mother Mary, which, if she were still alive, would have thrilled her to bits. It was the first and only time my mother and I have been together in a newspaper article and I will always treasure it.

Bellow is the text of the article for those of you who don’t subscribe to The Times newspapers but who have asked if they may read the piece. I hope you enjoy it.

The Sunday Times article

By Marjory McGinn

HALFWAY through a phone interview with Hollywood legend Donald Sutherland, for a story on the actor’s early days working at Perth Theatre, he suddenly asked if he could talk to my mother, Mary.

“Okay, if you like,” I said, slightly anxious, wondering how this would go.

I took the phone to the adjacent room in our Stirlingshire home (in Scotland), where my mother was watching TV. I’d pre-warned her that I’d be interviewing Sutherland and asked her to keep the TV low.

“Mum … Donald Sutherland would like to speak to you, from Los Angeles,” I said, handing her the phone.

“Me?” she said, her eyes wide with confusion.

She took the phone, her hands shaking, but said in her sweetest Scottish accent, “Well, hello, Donald!” as if they’d known each other for years.

It was one of the most bizarre episodes of my life. I sat in the corner of the room, listening nervously. The conversation went on and on, my mother giving the actor a guide to Perth streets and landmarks. Mary, 75, knew Perth well, as she’d been born there, as had I. And Sutherland was apparently lapping up her ‘guided tour’ of the city.

It came about because Sutherland and I had just been discussing the nine months he spent in 1960 honing his craft at Perth Theatre. Canadian-born Sutherland would quickly become the most famous member of the theatre’s dazzling alumni, which includes Sir Alec Guinness and Edward Woodward.

Sutherland – who died on Thursday, aged 88 – told me his time in repertory at the theatre had been his first big break in acting and had given him confidence. “It was like being married to a wonderful woman,” he said, descriptively. “It was the first time in my life where the audience actually laughed when I was being funny. That means a lot to an actor.”

Sutherland, who has Scottish roots, had loved Perth, but had little affection for the draughty flat he rented near the theatre. For some inexplicable reason he wanted to know where exactly it was. Did I know? No! And that’s where my mother came in, at my suggestion.

The pair then blethered on and on about everything to do with Perth: streets, shops, pubs, with me checking my watch constantly, wondering if my dear, affable mother hadn’t just hijacked the interview.

In the end I had to tap her gently on the shoulder and lure the phone back. Later, Sutherland told me he’d enjoyed talking with my mother, but whether they had discovered the whereabouts of his miserable flat was doubtful.

The interview with Sutherland was one of the most memorable of my journalistic career. He was an engaging, thoughtful, entertaining character. At the end of it, he gave me his private email address, in case I had other queries.

I emailed him not long afterwards, offering to send him an historic brochure given to me by Perth Theatre, including his repertory years. He was thrilled. He signed off his email: “My best to your mum and to yourself. Donald.”

Curiously, that was to be the start of a four-year, sporadic, email friendship with him. His missives were entertaining: quite formal to start with, sometimes candid, surprisingly tetchy, particularly when I asked him in 2003 if it was possible to interview him again for his upcoming film Cold Mountain, in which he starred with Nicole Kidman, a subject that was to prove contentious.

He replied: “Dear Marjory McGinn. It’s a little premature to start talking about Cold Mountain. The film’s in its first assembly. There’s a lot of work ahead.” In that email I also thanked him again for his kindness while chatting to my mother because she had since passed away. I wrote: “I wanted you to know that right up until she died, she told everyone she met about your conversation with her about Perth. It was one of the most enthralling moments of her life.”

He replied: “I am sorry about the loss of your mother. It was delightful for me to chat with her and I’m thrilled that she enjoyed it too. My best to you, Donald Sutherland.”

Later in the year I wrote to him again, and among other things, gently nudged him about a possible interview for the upcoming Cold Mountain. Even just a phoner.

“I don’t do phoners,” he replied a little petulantly, but surprisingly candid. “Our conversation on the phone (in 2000) was more a little chat about the far distant past. And I’m not going to be in England… But more than all of that. I’ve kind of pulled back into a shell here in Quebec and I’m not planning to give interviews to anybody. I’m too angry. Way too angry.”

Angry at what? Me for asking about Cold Mountain? It became obvious from some of his emails that he didn’t like his privacy being invaded, even though he’d given me his email address.

“Very few people have it. No print journalists that I know of, other than yourself. I trust you will respect the privacy of that address. I know you will anyway. I don’t know why I even bothered to mention it.” However, he finished off by saying: “My new pup is crying in the kitchen so I have to go look for her well-being. I hope you’re well and happy and I send you my best regards, Donald Sutherland.”

I immediately wrote back and apologised profusely for having, or so I thought, given offence over Cold Mountain.

He replied: “My God, you misunderstood, Ms McGinn. I’m not angry about you. Not at all. If I’d been angry, I would never have returned your email. I’m mad about this wretched government that’s doing its very best to ruin the world we live in. Terribly mad. And I don’t even have a vote. Good heavens no. Your letter was filled with affection. Donald Sutherland.”

The ‘government’ comment was a reference to the government in the US, where he’d been living, and its invasion of Iraq.

In early 2004, after finally seeing Cold Mountain, I told him how much I’d enjoyed it, but that his character, the patriarch, the Reverend Monroe, had died way too early, surrounded by his family.

His reply was self-effacing. It was the first time he’d referred to be by my Christian name.

“Dear Marjory. Thank you for your kind letter. I’m fine, still old and still being filmed dying with a bevy of beautiful daughters or grandsons or whatever! By the way, the pup is brilliant. Much affection. Donald Sutherland.”

I wrote to him in 2005 to tell him how much I enjoyed his latest film, Pride and Prejudice, in which he played Mr Bennet, but heard nothing back, and that was sadly to be the end of our correspondence. Understandable, with his heavy schedule of films. Or perhaps he felt the need to pull back into his ‘shell’ again.

I sensed through my fascinating correspondence with Sutherland that he was a peculiarly shy man, sensitive about his quirky looks. He told me during the 2000 interview: “People have considered my looks to be odd and I don’t think I’ll ever really come to terms with that, but they’ve given me a wonderfully delicious life, so I can’t complain.”

A touching admission, but women certainly were never averse to his looks, including his biggest fan, my dear mother Mary.

Marjory’s books

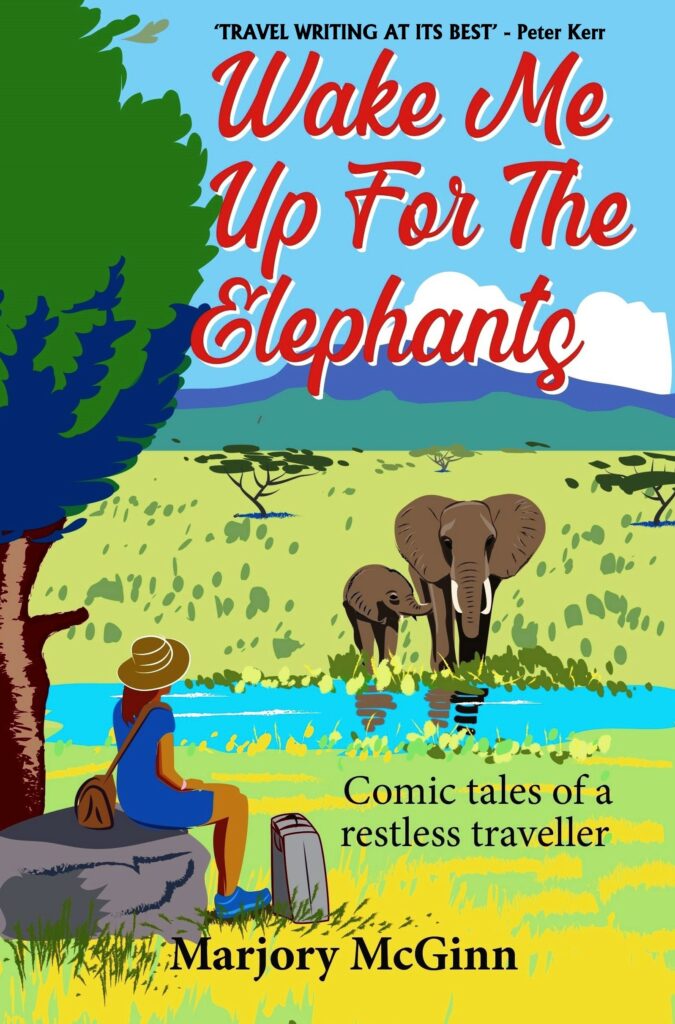

Marjory writes novels and travel memoirs mostly set in Greece. In her latest memoir, Wake Me Up For The Elephants is now published to great reviews. The book is funny and candid and described by Times best-selling author Peter Kerr as “Travel writing at its best”.

It has stories this time from very different places including Africa, Fiji, Australia, Ireland, Greece and Scotland. The Scottish stories include a comical and poignant Thelma-and- Louise-style account of Marjory’s holiday with her mother Mary. It’s a sentimental return to the homeland but full of funny mishaps and remote destinations including the Outer Hebrides and the far northern highlands.

Here’s a link.

https://mybook.to/WakeMeUpForElephants

For more information about Marjory’s Greek memoirs and novels, based on four years living in Greece, and to make contact with the author, which is always welcome, go to her website: https://www.bigfatgreekodyssey.com

The author also has a new writer’s page on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/MarjoryMcGinnWrites

Thanks for dropping by.

© All rights reserved. All text and photographs copyright of the authors 2010-2024. No content/text or photographs may be copied from the blog without the prior written permission of the authors. This applies to all posts on the blog.