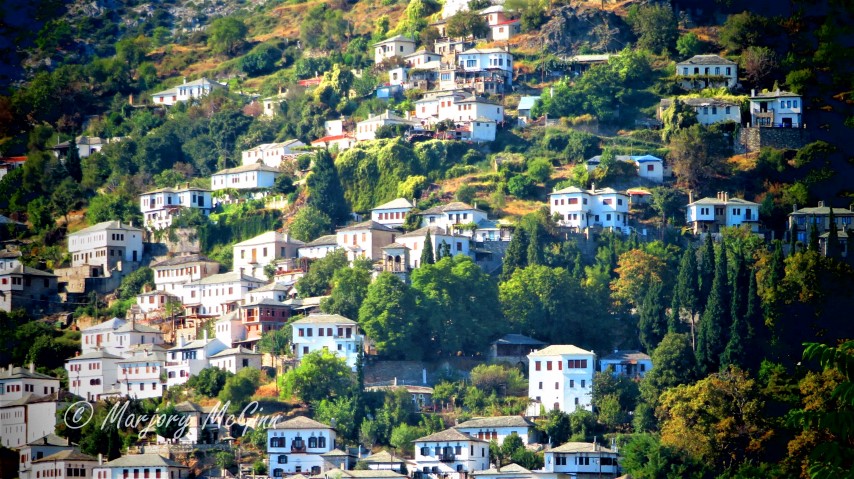

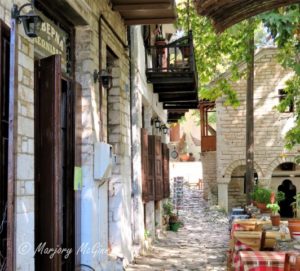

Unique Makrinitsa village in the Pelion mountains

IT’S always a nervy experience, arriving at a Greek destination late at night, one that’s completely new to you. Jim and I landed at Volos airport, in the Pelion region, around 10 o’clock one hot August night last summer. Half an hour later we were still there, sitting at a coffee table outside to see the young hire car guy. There was a small queue and the coffee shop was his ‘office’. It all seemed to take ages, but the guy was genial and after all the paperwork was signed he explained how to get to Volos city, around 20 miles away at the head of the Pagasitikos Gulf.

We had booked a room in the Volos Palace Hotel, with the intention of an early start the next day, driving down to our rented villa in south Pelion. We had brought our sat-nav along because we planned to do a lot of touring around the long Pelion peninsula. The hire car guy blithely waved us off and we headed towards the bright lights of Volos in the distance, nestling in front of the brooding western flank of the Pelion mountains. What could possibly go wrong? Well, everything really. This was Greece, after all, a country that we knew – after four years living in the southern mainland – could spin you a curved ball at any time.

The journey started off okay, until we reached the motorway exit for Volos. It was closed for road repairs. Why hadn’t the hire car guy mentioned this? Who knows? We had to keep heading north on the motorway, which was not where we wanted to go. A few diversion signs on the way weren’t helpful, as Volos didn’t seem to figure in any of them. On we went, becoming more and more lost, the poor sat-nav announcer woman yammering out unfathomable requests as the night was slipping by.

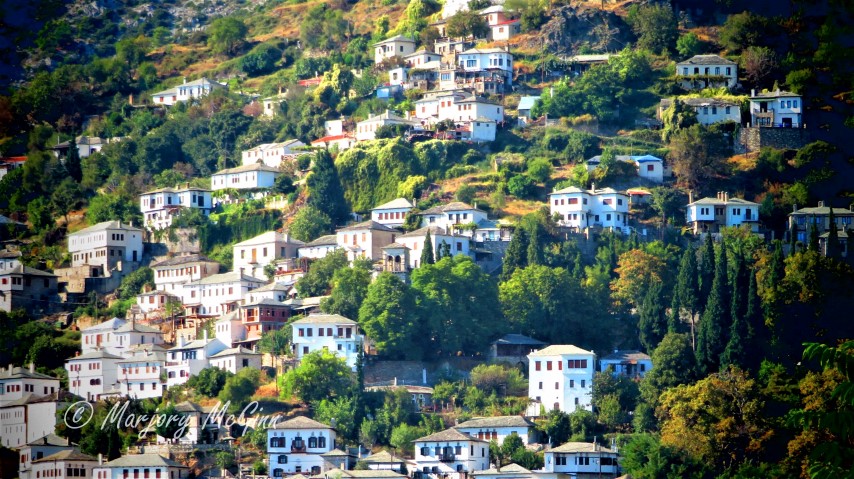

The view down to Volos from Makrinitsa

We did find a place to turn around in the end, and headed south again. By sheer luck we spotted an exit ramp marked Volos. Jim punched the air with relief as we drove towards the western edge of the city. But when we got there, we faced even bigger problems. Every road into the city seemed to be having road repairs on some part of it, with closures and yet more diversion signs and traffic cones. Why would the city fathers want to do this in August, the busiest month in Greece?

We began a tormenting, rubber-burning foray into the city and out again (so many times we lost count) desperately searching for the road (any road!) that would lead us to the hotel, near the port area. No point in stopping pedestrians because I’ve found the Greeks (God bless them) are like the Irish with their left-field directions. It’s diverting and funny, but always gets you into more strife.

We could actually see the top of the Volos Palace Hotel twinkling in the distance like a siren on a rock, but we could never quite reach it because of the roadworks, and we had to concentrate more on Greek drivers (equally frazzled) pulling maverick stunts, especially on roundabouts. It was now nearly midnight. We were exhausted and hungry, and Jim resorted to a few strops (unusually for him) at the wheel. The sat-nav woman had also gone off her trolley, a gibbering wreck by now, spitting out instructions that she instantly cancelled and updated every 10 seconds, and all in her crazy, mispronounced Greek.

At one point she pleaded pointlessly for us to try for the “Lambro Gorilla”, which sounded like a Latin American dance move, or a strong cocktail. We’d have killed for a cocktail by then, if not a hot Lambada. In the end we silenced her.

Volos has a strong café society

We were close to giving up, dumping the car on a street near the hotel and lugging our suitcases there on foot, when a young couple swung by. I wound down the car window and pleaded for their help. The girl told us to forget the “crap” sat-nav (how did she know?) and explained the best route to the hotel. It was a bit tortuous but we finally arrived at the hotel, even snagging a parking space outside.

The four-star Volos Palace looked plush on the outside but inside it seemed like a relic from another era (well before Greece’s economic crisis), with plenty of marble and swish curtains. But it seemed tired, just like the guy on reception. We were at wit’s end when we asked him about room service (having eaten our last modest meal eight hours previously) and were told emphatically ‘no’. “All the catering staff have gone home now.” What in August? Midnight in Greece, in August, is only just time to put the kids to bed, or head out to dinner to eat and then dance around in circles til 4 in the morning, in our experience of high Greek summer.

There seemed to be no-one in the hotel, apart from a few bleary residents hugging the bar, watching a football game on TV. We were given a city map, however, and shown where we could find a ‘lively’ street with a huddle of tavernas.

Replica of the ancient Argo ship

On the map it looked easy but in reality it was a longish walk beside a wide busy road (not blocked!), and as we trudged along we discovered finally what a Lambro Gorilla was. It’s a major road to the harbour area called Grigoriou Lambraki, named after a 1960s Greek hero, which the sat-nav minx had got back to front as well. We had a good laugh wondering why the hell we bothered with sat-nav and all that flaky euro-bla-bla.

Those who have read my third travel memoir, A Scorpion In The Lemon Tree, may remember our other experience of crazy sat-nav instructions – same contraption, same minx – when we were driving in southern Greece. She kept warning us about ‘calamitous coronaries’ and other dire disasters on the road from Kalamata to Koroni. Time for a new sat-nav.

We were beyond tired when we saw signs of life: a street with a row of cafes and a souvlaki joint still buzzing, which is usual on hot nights in Greek cities. It had a nice vibe, with a few tables and chairs on the pavement, people sitting about still eating. This was more like it. The staff were helpful, bringing us not only two servings of souvlaki wrapped in warm pita breads but little bowls of salads and Pelion specialties, which we hadn’t ordered. And a couple of cold Mythos beers. For the first time since we’d arrived hours earlier, we felt our shoulders drop with relief, and we tucked in.

We mentioned the road block disaster to the owner. He grimaced and waved one arm around in the diverting fashion of Greeks when they’re hacked off over something. “No one knows why the council does things this way. Ridiculous!” he complained. Just another imponderable to add to the load of crisis anxieties this country has faced for years. But despite everything, it’s the human touch, which Greeks have in abundance, as well as their conviviality, that makes you love this country and keeps you coming back.

View from the tip of the Pelion peninsula

The next morning, after a hearty hotel breakfast (the staff were back!), we had recovered from our arrival anxieties, though I can’t say we felt rested because all night long from our front room we could hear people trudging up and down the street going home, singing old Greek songs, talking loudly in huddles, shouting “Chronia Polla!” (a common Greek wish, “many years” for birthdays etc). This was August party mode of course, that had seemed lacking on check-in, now played out at full volume. But at least the drive south from Volos was a dream.

The views of the long gulf reminded us strongly of the Messinian Gulf, with Kalamata at its head, with a series of small coves along the coast. Pelion is a rather magical region about four hours’ drive north of Athens. The other side of the peninsula faces the Aegean Sea close to the islands of Skiathos and Skopelos. Some of the beaches on this side, especially in the north, are stunning, like Papa Nero and Damouchari, where some of the beach scenes in the first Mamma Mia movie were filmed.

Paltsi, one of the Aegean beaches on the east coast of the peninsula

It’s a unique region dominated by the Pelion mountainous in the north, fabled in ancient times as the home of the legendary centaurs (half man/half horse) and called the “Mountain of the Centaurs”. Volos city is believed to have been inhabited since 700BC. There have been Neolithic and Mycenaean settlements here and a trip to Volos’s Athanassakeio Archeological Museum is a must, with its small but perfect collection of antiquities.

View of the gulf, Tiseo mountains and island of Palia Trikeri

We had booked a villa for a month just south of the small town of Argalasti, close to the gulf side with stunning views towards the Tiseo mountains in the south. We planned to spend the first week or two exploring beaches while the weather was hot and the sea calm, and then make a few excursions into the Pelion mountains to visit some of the more traditional villagers tucked into the mountain slopes, such as Makrinitsa, Milies and Tzagaratha.

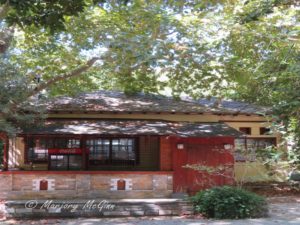

Yiorgos Koutzifelis in his traditional store in Argalasti

Old bottles of retsina from the 1950s

Argalasti is the main town in this part of the peninsula and a good base for exploring the region. The town is very appealing, with a central old-style plateia, square, under plane trees, which is rimmed with cafes, tavernas and shops, like the traditional general store run by Yiorgos Koutzifelis, whose family have owned it for several generations. On one of the high shelves Yiorgos pointed out his prized bottles of retsina dating from the 1950s, not for sale of course. In mid-summer the town is fizzing with visitors, but off-season it’s very Greek and its square reverts back to a lively local hangout.

It attracts people from the surrounding area and even the odd person of dubious importance like Boris Johnson’s father Stanley, who owns a plush villa in the hills behind the town, where Boris had a much-publicised love tryst with the new, young, woman in his life, a week or so ago. We saw Stanley shambling down a hill one day, with bulging shopping bags in each hand, and showing the family propensity for shabby-chic couture and muppet hair. But celebrities are the least attractive aspect of the Pelion, to my mind.

The fishing village of Ayia Kyriaki

The further south you drive on this peninsula the more the area has an island feel, very wound-down and easy. The tip of the peninsula hooks up at the bottom like the tip of a scorpion’s tail. With the backdrop of the Tiseo Mountains lie some remote villages, like Trikeri, and Ayia Kyriaki, an old fishing settlement still thriving with a huge flotilla of traditional Greek caiques and a row of excellent fish tavernas by the water.

The place where we ate lunch seemed like a trendy spot for a remote village. At the table next to us, a stylish couple, dressed for an Oscar awards night, set up a tripod and camera and filmed the whole of their lunch, complete with serious dishes of seafood, without hardly saying a word. Why, we don’t know. But somewhere on that film there must be background footage of a scruffier, slightly more lively couple, devouring their calamari and Greek salad and toasting their latest holiday in Greece. Fame at last!

Tzasteni is simply one of the most photogenic beaches in Greece

A few miles north on the gulf side is the gorgeous and colourful Tzasteni, which has a promontory on one side of the cove with renovated white houses, once owned by fishermen no doubt. This was an idyllic spot with a narrow sandy beach which improved even more as September wore on when there were fewer yachts and other craft, lured to this beauty spot, dropping anchor just off the beach. I wouldn’t recommend it in high summer, but off-season – perfection.

The elegant square in Makrinitsa

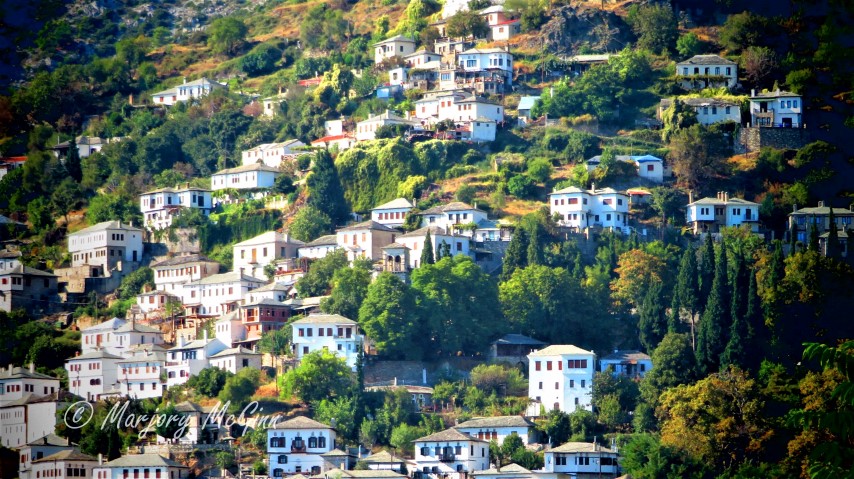

A mountain village seen from Volos

Some of the best places we visited in Pelion were the mountain villages, of which Makrinitsa was the most memorable, partly for its dizzying view down over Volos city and its old-fashioned style. As an official area of ‘cultural interest’, and therefore protected from modern development, it has probably changed little over the centuries and owes much to its wealthy trading past, with grand buildings in classic Pelion style: a mix of local stone at the bottom and mudbricked, whitewashed upper floors (for summer use). The square is stunning, shaded by giant plane trees with excellent tavernas and cafes on its periphery. The best tables are on the edge with the dizzying view down towards Volos.

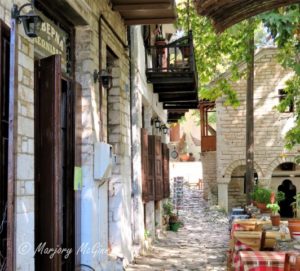

A cobbled path near the square with the Leonidas taverna

Detail from a famous Theophilos mural in a Makrinitsa cafe

We had lunch just off the square in the Leonidas Taverna, a traditional place on a small cobbled pathway with a few tables outside overlooking the square. The meal was delicious and simple and it was next to one of the village’s most famous hangouts, the Café Ouzeri Theophilos, named after the famous folk artist Hatzimihalis Theophilos, who frequented this place and painted a fresco over one wall with the theme of the 1821 Greek War of Independence. You really do feel the weight of Greek history and culture in this village.

Sitting room in the Makrinitsa museum dating back to mid-19th century

One of the best places to go here, if you have the time and inclination because it’s a bit of a walk down one of the famed cobbled (kalderimia) paths, is the Museum of Folk Art and History of Pelion, situated in the former mansion of a wealthy merchant and built in 1844. Since it was taken over by the Ministry of Culture from the Topali family 20 years ago, the house has been restored but kept as the residence used to be, with all its historic grandeur. It is simply stunning. There are riches galore in this place, from folk art to traditional rugs, costumes, embroidered saddlebags, paintings, historical artefacts from the War of Independence, and much more.

The charming guide Kostas Patsiantas likes to entertain visitors with an old gramophone in the village museum

The museum was just about to shut when we got there but the guide, a young guy called Kostas Patsiantas, was incredibly generous in keeping it open a while longer and gave us a special guided tour. He was particularly knowledgeable about the village’s own 1878 revolution against the Ottoman Turks and there are interesting artefacts here, including a painting of the idealistic British journalist and philhellene Charles Ogle, who was murdered in the village by the Turks.

There is much to see in Makrinitsa and it’s worth staying a couple of days. There are plenty of hotels, and if you don’t want to drive there’s regular transport from Volos bus station up all those steep windy roads – it takes about an hour.

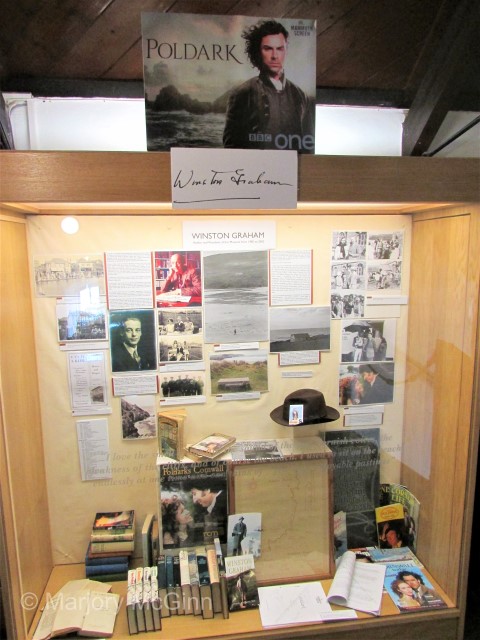

Jason and the Argonauts left Volos on this ship seeking the mythical Golden Fleece

Volos itself was also a revelation. After our snarl-up on the way in we probably had poor expectations of what it had to offer, but we drove back several times and couldn’t have been more wrong. We thought it was one of the loveliest cities in Greece, very laid-back and easy to navigate, on foot at least, with a large pedestrianised shopping area, a buzzy café society in the centre and a large choice of places to eat and drink. Our favourite taverna was the trendy Ouzo Therapy at 230 Ermou Street (www.ouzotherapy.gr), which was bursting with Greek families on the Saturday we went, with every table booked. The food is exquisite, with nice touches like green salad with sundried tomatoes, walnuts and balsamic vinegar. The seafood was divine.

Happy hours in Volos at the popular Ouzo Therapy restaurant

The city is full of art galleries and museums. There is a wooden replica of the legendary Argo ship next to the seafront promenade. It was from this city in ancient times that Jason and the Argonauts set off, seeking the mythical Golden Fleece.

There are some unusual shops in the shopping precinct. My favourite was the lovely art jewellery shop called Voulgari, one of those traditional shops so hard to find in Greece now if you like folk and arty jewellery that is local and handmade with unique designs. The shop is owned by artist Vasilia Voulgari, a delightful woman who produces her own pieces from mostly silver and semi-precious stones. They are exquisite and very reasonably priced. Voulgari’s, 18 Glavani Street (near Ermou Street). Tel: 24210 31626.

For more info about Volos www.volosinfo.gr

On the next blog I will continue my narrative on Pelion, on some very different kinds of villages, some thriving and authentic, some definitely not. And I look at a few more of the remote mountain settlements with surprising riches, like one of the oldest and most curious libraries in Greece. See you then.

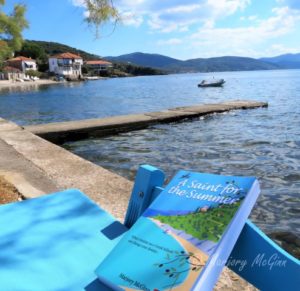

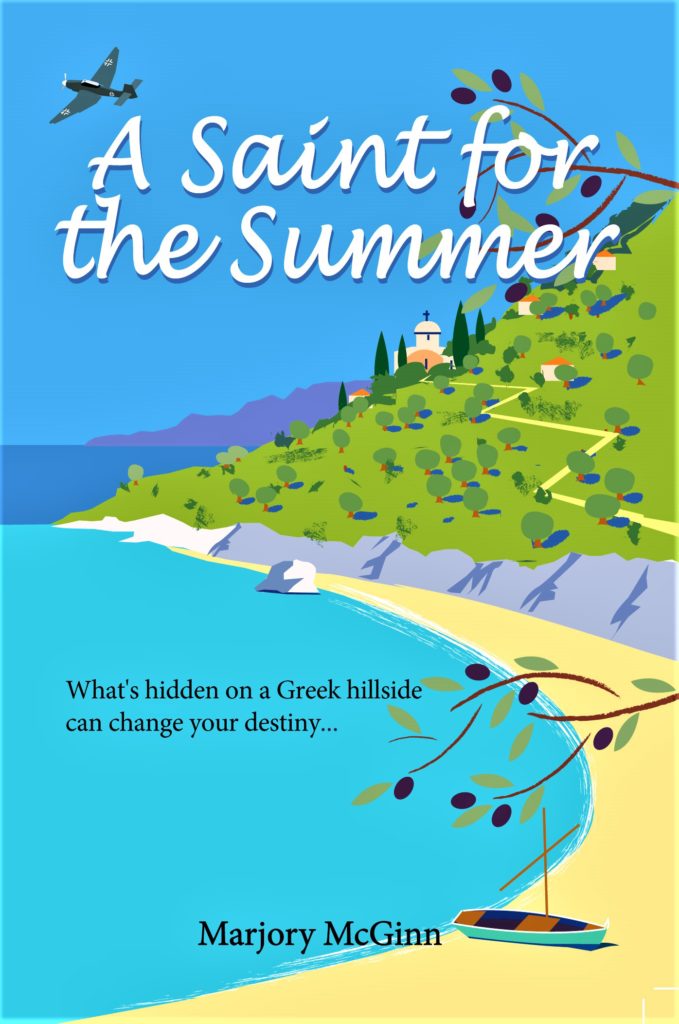

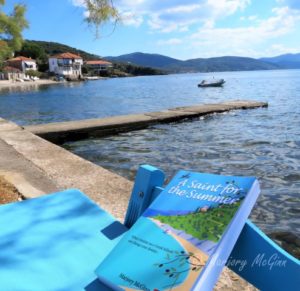

Novel set in Greece

My first novel, A Saint For The Summer, set in southern Greece, is my latest book, following my Peloponnese trilogy of travel memoirs. It’s is a gripping contemporary story but with a narrative thread back to the Battle of Kalamata in the Second World War. On a trip to Greece British Journalist Bronte helps her expat father to sleuth out a family mystery: what happened to her grandfather who disappeared during this infamous battle that has been called “the Greek Dunkirk”.

“This story will renew your faith in mankind.” WindyCity online magazine, Chicago.

The book is available on all Amazon sites and through Barnes & Noble. For Greek readers through the www.public.gr stores.

Here’s an Amazon link: https://bookgoodies.com/a/B07B4K34TV

If you have read my books and liked them, please think of leaving a small review on Amazon. It will be gratefully received. Thanks.

For more information about Marjory’s books visit the books page on our website www.bigfatgreekodyssey.com

Or visit Marjory’s books page on Facebook

Thanks for dropping by. All comments are gratefully received. Just click on the ‘chat’ bubble at the top of this page.

© All rights reserved. All text and photographs copyright of the authors 2010-2019. No content/text or photographs may be copied from the blog without the prior written permission of the authors. This applies to all posts on the blog.

Like this:

Like Loading...