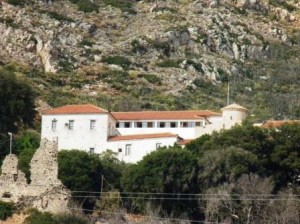

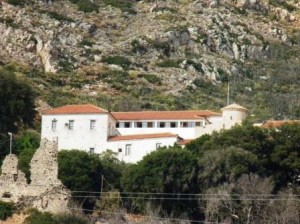

Dimiova women’s monastery high up in the Taygetos mountains in the southern Peloponnese

IT was sad indeed to hear of the death of one of the last two nuns at the unique Dimiova monastery, east of Kalamata, in the southern Peloponnese. Sister Christina, in her seventies, died last December after a long illness. I had met her and the Abbess of Dimiova, Sister Kiriaki, during a day-long ‘retreat’ at the monastery in 2012 and subsequently wrote a blog piece about my memorable experiences there.

With only the Abbess remaining now at this remote place high in the Taygetos Mountains, the future of this outstanding monastery, which houses one of the most revered icons in this part of the Peloponnese, will now be in doubt. There are only a handful of working monasteries left in this region, particularly for women.

During lunch that day at the monastery, it was Sister Kiriaki who remarked that the economic crisis had impacted drastically on the monastery, on its much needed repair and renovations and its ability to support more nuns. The two remaining nuns had been leading very humble, restricted lives even before the crisis began, but now the situation was much bleaker, as it has been for most priests as well in the Orthodox church, and the churches themselves.

In a few short years, the lack of funds throughout Greece will mean that many old monasteries will have to close their doors, apart from the highly visible and protected monasteries of Mount Athos. Already in the southern Peloponnese many have closed, due to lack of staff or because they are becoming derelict.

In a modern world where religion has less significance for many people, a common complaint (even from younger Greeks as well) is: “Why do we need monasteries?”

The Orthodox religion is an integral part of the vibrant Greek culture, but the issue goes beyond religion I think. These Greek monasteries, and many churches, are unique historic buildings and contain a wealth of outstanding Byzantine frescos that are surely as important to European art tradition as any Italian Renaissance masterpiece. Painted on the interiors of churches, often open to the elements, the frescos are fading and in need of regular upkeep, now mostly impossible in the crisis. If you are lucky, you might see inside one of these establishments once or twice a year on certain saints’ days.

The monasteries are also an enduring part of the communities that surround them and have, during difficult periods of Greek history protected communities, hidden Greek freedom fighters and have promoted the Greek language and its culture. If these great institutions close, and finally crumble into ruins, it will become near impossible to revive them in future decades.

One day in the future, Greeks will surely climb out of the economic crisis, but without these splendid historic and religious monuments, the country they inherit will not be the one we know today. And that would be a tragedy.

To give an idea of how special Dimiova is, I am posting here a slightly shortened version of the blog I wrote in 2012. If you feel strongly about the subject, do please leave a comment on the post.

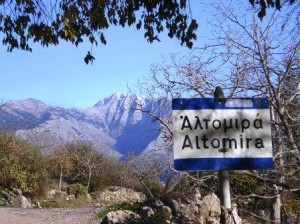

WHEN my friend Gillian Bouras and I hit on the idea of going on a short retreat to the monastery of Dimiova, in the Taygetos mountains (southern Peloponnese), the plan had great appeal. Friends said we were crazy, but undeterred we went ahead with our strategy for a trip in early August in the lead-up to one of the holiest dates in the Orthodox calendar, the 15th of that month, which is the feast day of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary.

Gillian is an Australian-born writer who has lived in the southern Peloponnese for over 30 years and has written extensively about it. We both had slightly different expectations for this jaunt but what we did have in common as writers was being able to gain access to this traditional and rarified way of life, still shrouded in centuries of Orthodox mystery, before it disappears altogether in Greece. At Dimiova, in the remote northern western slopes of the Taygetos, sadly there are now only two elderly nuns left.

The church dedicated to the Dormition of the Panayia at Dimiova was built in the 17th century

The preparation for this short trip was more protracted than I would have guessed. I had to enlist the help of a Greek friend who had contacts within the Greek Orthodox Church. Because monasteries are highly respected and guarded here, we needed authorisation from the head of the church for the Messinian region, Bishop Chrisostomos. And after many weeks of waiting, we were gratefully given the go-ahead.

Two weeks before the visit we were also required to meet Papa Sotiris in the hill village of Elaiohori. He was co-ordinating our trip and also takes the Sunday services at Dimiova and oversees its ecclesiastical well-being.

Papa Sotiris is a genial young priest with a modern outlook. Having worked previously as a businessman in Kalamata city, he gave up his career to join the priesthood, despite the fiscal sacrifice that entailed, and has not had one moment of regret. He was delighted (and a little intrigued) by the request to visit Dimiova, but there were certain conditions.

We had to be at the monastery 7am sharp. The clothing rules were strict: sensible dark/black clothing – long skirts, no bare arms or legs, sensible shoes, no bling of any kind. We were told the nuns led a simple and somewhat severe life, that they would be adhering to a semi-fast on the lead-up to August 15. The most vexatious rule was saved for last. There would be no talking at the monastery. No talking?

Although talking is not strictly forbidden, Papa Sotiris told us the nuns don’t like to talk unless they have to, especially at this devout time of the year. But since we wanted to write about monastery life, the no-talking rule was awkward.

“How will we be able to glean anything about the nuns’ lives if we can’t talk to them?” asked Gillian.

We were simply to find that out for ourselves, Papa Sotiris seemed to indicate rather mysteriously.

****

The Abbess Sister Kiriaki, left, Papa Sotiris, the priest at Dimiova, and Sister Christina

IT’S Friday morning at 6am when set off on our pilgrimage and it promises to be another scorching August (38C) day. The drive up the winding road with hairpin bends, occasionally with a scattering of rocks, from a recent unseasonable downpour, sets the right kind of reflective tone and we are both secretly wondering if we aren’t crazy after all with this monastery expedition.

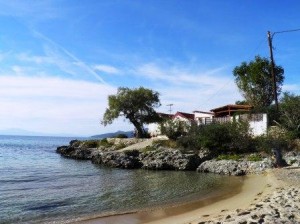

The last few hill villages are left behind as we drive further into the Taygetos, having passed no other vehicle along the road, or seen another soul. But Dimiova, when it comes into view, tucked into a mountain slope, surrounded by fir and pine trees, is bigger than expected. The outer walls and monastery buildings are white and the tiled, domed roof of the church is poking up from the inner courtyard like a jaunty hat. I am now anxious to get there as I bump the small Fiat car painfully up the last steep, boulder-strewn metres of dirt road to the front gates.

A morning service has just started in the monastery church, dedicated to the Dormition of the Panayia (Virgin Mary). A bell tolls and the sound of the liturgy is sonorous and spine-tingling in this lonely mountain location. At the door of the church we are met by Sister Kiriaki, who is also the Abbess of the monastery, whom we are relieved to find does talk (though not volubly).

But she has rather charmingly forgotten why we are here or what they are to do with us. She looks a little weary but at least the modest bags of cold drinks and fruit we offer as gifts for our stay are met with a smile. The large watermelon is given an especially warm appraisal.

She ushers us into the church beside the other remaining nun, Sister Christina, who is wearing a similar long black robe, her head wrapped in thick long black scarf. Kiriaki returns with offerings of her own, prayer ropes called komboskini, comprised of thick knotted wool interspersed with small beads (rather like a Catholic rosary). We are to hold these during the service, taken by Papa Sotiris.

The church is a lovely example of early 17th century design, with frescos painted in 1663 by the monk Damaskinos. The main focus of this church however is the old and much revered icon of the Virgin Mary (Panayia Dimiovitissa), and Child, which is claimed to have miraculous powers, as are many icons dedicated to the Panayia, though this particular icon attracts many pilgrims from all over Greece at this time of year.

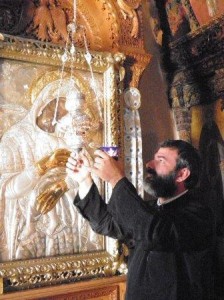

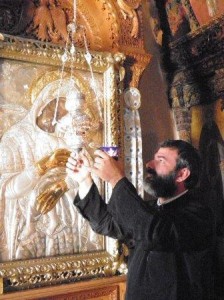

Papa Sotiris, top, lighting the votive lamp in front of the icon of the Panayia Dimiovitissa. Above: the icon showing the bloodstain on the Virgin Mary’s face

The icon is best known for the curious mark on the Panayia’s right cheek, which is said to be a blood stain, and there are many theories as to how it came to be there.

Papa Sotiris at the end of the service explains a little of the history of the icon and tells us it is the general belief that the icon was damaged by a sharp blow with a knife or axe during the struggles of the Iconoclastic period of Greek history (8th to 9th centuries AD), when many icons in Greece were defaced or even burnt.

The icon, he says, had been brought here for safe keeping some time in the 8th century, when the first monastery building was erected, and during a violent skirmish between the defenders of the icon and interlopers, the image of the Panayia was struck and blood sprang from her face. The signs of it remain today, hence its miraculous powers.

The monastery of Dimiova has always been one of the most important of the Messinian region and has a gripping history. During the 15th century it was set on fire by the Turks during a local skirmish and rebuilt a century later, only to be attacked again by the Turks in 1770.

However, it survived and became a meeting place for some of the great revolutionary leaders in the Greek War of Independence against the Turks in 1821. It is said that some of these leaders, like the heroic Theodoros Kolokotronis, plotted the opening shots of the war, started in Kalamata on March 23, from within these hallowed walls.

The monastery is best known in Messinia for its annual procession (started in 1843), and the carrying of the icon from the monastery down to a church of Giannitsanika on the edge of Kalamata, a journey of over 13km, which takes around five hours.

After the service, Papa Sotiris offers us Greek coffee with several other parishioners in one of the lovely old dining rooms in the monastery. Despite the no-talking rule, Kiriaki, at least, is in good conversational form, perhaps enjoying a respite from their solitary life. Kiriaki is in her mid-sixties yet looks much younger with a fresh, unlined face.

Kiriaki’s story is not an unusual one in Kalamata. After the Second World War, along with many other war orphans, she was left, aged two, under a certain plane tree near Kalamata Cathedral. The convention was that youngsters were left here to be taken in by kind Kalamatans, but in Kiriaki’s case she was taken to Dimiova.

She has known no other life but this. It’s a fairly regimented existence, with a 5.30am start for prayers, a simple breakfast (they only eat twice a day) and then work in the fields and gardens, tending the monastery’s flocks of sheep and goats, cooking, and then retiring at eight or nine o’clock, depending on the season.

The winters here, says Papa Sotiris, are long, cold and dark, with very simple accommodation and heating. They have no TV, no computers and only one radio tuned into an Orthodox religious station.

“The nuns are allowed to speak if they want to,” explains Papa Sotiris, “But most of the time they choose not to. They find it peaceful not to talk.”

“They are like two canaries in a cage,” he explains with an ingenuous flourish, “It’s a lovely cage though, a lovely environment and they don’t want to fly out into the outside world.”

To us it seems a bit lonely and yet once it would have been otherwise. When Kiriaki was a child there were a few dozen nuns in residence, and earlier in its history, as a monastery for monks only, it was capable of housing up to 100 people. Over the years, though, as the older nuns have died, the numbers have not been replaced.

Many people come to Dimiova primarily to see the miraculous icon and it is kept under lock and key for most of the time. In this region there are many stories also about its miraculous powers.

Papa Sotiris says: “There have been many, many stories in the nearby villages of people experiencing miracles. Everyone has their own special story.”

The miracle that needs to befall the monastery at the moment, sadly, is funding. The monastery buildings and the church, which were partially damaged in the earthquake of 1986, are in constant need of maintenance and restoration. The monastery is always grateful for public donations, however small, to help this cause as one of the few working/occupied monasteries, for women in particular, in the Messinian region.

Over a simple but tasty lunch that day of black lentils with onion and sturdy village bread, Kiriaki tells us the monastery is suffering in general from lack of funds, like other church institutions here, because of the economic cutbacks in Greece.

With restoration work on some Byzantine churches, particularly in rural areas, already being scaled back, the future of monasteries like Dimiova and the gentle souls who inhabit them is more in doubt than ever.

Sister Kiriaki, top, hitting the traditional wooden talado, which is used to call the faithful to prayers or for meals. Above: Sister Christina in reflective mood

When we finally take our leave much later after the lovely esperinos, the evening service, for the long nerve-pinching drive back down the mountain, we are told to come back soon and are given more gifts of filakta, small embroidered pouches smelling of lavender, which, whispers Kiriaki in my ear, are to be worn near the heart “for protection”.

The flower garden in the monastery grounds is a place of gentle reflection

All the way down the mountain road in the fading light I feel sleepy with the heat but I have to keep my eye out for more scree over the road, but luckily it’s all clear. Neither of us feel inclined to talk, lost in our own thoughts.

Apart from the heavenly mountain setting and the history of the place that you feel in every well-worn corner of Dimiova, for me it is the two lovely nuns who are the spirit of the place. And unexpectedly inspiring.

At a time when Greece is rocked by harsh austerity measures, job losses, rising suicide rates, and loss of confidence, here are two people uncomplaining about a life pared down to the bone. Their simple life and their serenity has a way of cutting through all our modern worries like that church bell tolling down a deserted mountainside at seven in the morning.

* Donations for the church are gratefully received. Information about Dimiova through the Metropolis of Messenia www.mmess.gr

A longer version of this blog post formed the basis for the Chapter, Touching Heaven, in my second travel memoir Homer’s Where the Heart Is. For more information about this book and the first memoir Things Can Only Get Feta about my three years living in the southern Peloponnese, go to www.bigfatgreekodyssey.com/blog or order through www.amazon.co.uk

@ Copyright, text and photographs, Marjory McGinn 2016

Like this:

Like Loading...