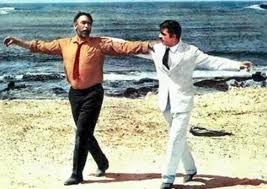

APART from the Parthenon, Nana Mouskouri and blue-domed churches, what image or event totally captures the essence of Greece? For me, it’s the cinematic images of Zorba, played by Anthony Quinn, dancing the sirtaki on the beach to the Mikis Theodorakis’s theme tune – Zorba the Greek. The outrageous, lovably raffish Zorba is the enduring symbol of the nation’s spirit and stoicism. It’s no accident that during the international campaign earlier this year called We Are All Greeks, sympathisers world-wide took to city streets, linked arms and danced the sirtaki in support of Greece.

The character of Alexis Zorbas that Nikos Kazantzakis created 60 years ago in his book The Life and Times of Alexis Zorbas (translated into English as Zorba the Greek) is more than just a literary concoction, however. The real man behind the character was every bit as spirited. Legendary tales about him are kept alive today in an unspoilt corner of the Mani region in the southern Peloponnese.

It was here that Cretan-born Kazantzakis hooked up with Yiorgis (George) Zorbas in 1917 for a peculiar and risky venture in lignite mining that was doomed to failure for many reasons but was nevertheless spun into literary gold a few decades later.

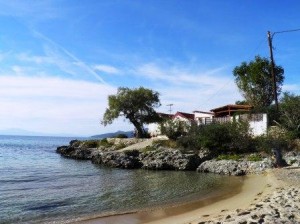

The original small white house at the end of Kalogria beach rented by George Zorbas from a local family

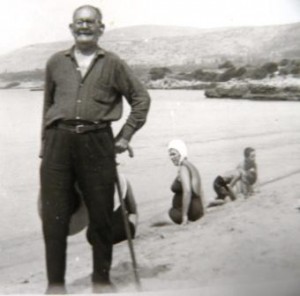

To find out more about the real Zorbas, we set off for the secluded beach of Kalogria, near the village of Stoupa, to meet a young woman called Mary Georgilea, whose family have been closely associated with the Zorbas family for several generations.

She took us to the small renovated house on the beach, built in the late 19th century by her great–grandfather Andreas Exarchouleas (pictured below) and rented out to George Zorbas when he first came to the Mani to be foreman of the Prastovas mine on a nearby hillside where Kazantzakis had become one of the partners in this venture. This was a time when the Greek government was offering incentives to mine lignite, a precious commodity in the war years.

The beach of Kalogria these days, out of season, is almost as deserted and peaceful as it was when the pair first came here in 1917. The small house with a red pitched roof is one of a pair built on the far right of the beach, not far from the well-known natural spring, the Prinkipa, that bubbles up cold mountain water between the rocks, like a natural plunge pool.

Mary Georgilea in front of Kalogria beach. Her great-grandfather Andreas Exarchouleas (below) rented out the white house to George Zorbas (bottom)

Kazantzakis had chosen to live on the other side of this quiet sandy cove from Zorbas in a simple hut made of wood and bamboo with nothing much inside but a table, chair and a straw-filled mattress. Yet it was here he spent much of 1917/18 writing and reading, leaving the gregarious Zorbas to deal with the lignite business, and village life.

Born in west Macedonia in 1867, Zorbas had worked in various countries as a miner before he came to the Mani, bringing his wife and some of their eight children with him, though they preferred to stay well away, living in the nearby city of Kalamata.

After working hours, Zorbas, then in his fifties, and Kazantzakis, in his thirties, regularly decamped to the shoreline of Kalogria with their supper – often cooked for them by a member of Andreas Exarchouleas’s family – for a long party session, either alone or with whoever had dropped by for the evening, over a few carafes of local wine, and Zorbas would play his bouzouki and sing. In real life, George Zorbas played the bouzouki, not the santouri, as in the book. The pair were famous locally for their rowdy beach soirees, in which they frequently danced along the shoreline, a fact that was immortalised in Kazantzakis’ book.

Mary, who lives in the nearby village of Stoupa and runs a villa rental business with her mother, was brought up hearing many outlandish stories about Zorbas from her grandfather, Yiorgos Exharchouleas, a well-known local resident. She says Zorbas was a unique character and faithfully captured in Kazantzakis’ book.

She also says that Zorbas and the writer more or less took over Kalogria beach in 1917 and scandalised and delighted Stoupa with their bohemian lifestyle. Stoupa in those days was a small, conservative fishing village with a few tavernas along the seashore and had seen nothing like this pair of outsiders, or their visiting friends – a cast of exotic international characters who descended on Kalogria beach and included famous Greek actors, intellectuals and one of Kazantzakis’ best friends, the poet Angelos Sikelianos.

But while Kazantzakis was a more reclusive and complex character, the locals instantly took to Zorbas’ antics, his bouzouki playing, his kefi (high spirits). Kazantzakis, as in the book, was the total opposite of Zorbas, the cultivated aesthete compared to the rough and ready miner. It was the most unlikely of friendships, yet Kazantzakis has written many times of his admiration and brotherly love for Zorbas.

In another of his books, the autobiographical, Report to Greco, Kazantzakis explains what Zorbas meant to him.

“For he had just what a quill-driver needs for deliverance: the primordial glance which seizes its nourishment arrow-like from on high; the creative artlessness, renewed each morning, which enabled him to see all things constantly as though for the first time, and to bequeath virginity to the eternal quotidian elements of air, ocean fire, woman, and bread; the sureness of hand, freshness of heart, the gallant daring to tease his own soul, as if inside him he had a force superior to the soul…”

To complete the search for the real Zorbas, Maria took us to the abandoned Prastovas area on a Stoupa hillside which has the original lignite mine the pair were involved in. The mine proved unsuccessful and had an early demise and now it is a rather wild and forlorn rabbit warren of tunnels oozing puddles of spring water.

The work at the mine had been hard and dangerous with around 200 workers employed in 1917, some of whom later remarked that while Zorbas was always there working like a mule, Kazantzakis was rarely ever seen, even in the stone ‘office’, that is now a dilapidated old house. He preferred to keep a quiet vigil at the beach hut at Kalogria.

Some of the local Greeks we spoke to about the legendary George Zorbas lamented the disappearance of great characters like him and say the economic crisis has cut the Greek hero down to size. But if ever Greece needed another unique, maverick soul like Zorbas – it’s definitely right now.

Report to Greco by Nikos Kazantzakis (Faber and Faber) translated by PA Bien.

A book about living in Greece

For more details about my book, Things Can Only Get Feta based on three years living in the Mani, southern Greece during the crisis, visit my website www.bigfatgreekodyssey.com or visit Facebook www.facebook.com/ThingsCanOnlyGetFeta

Visit Amazon to buy the book

For more information about the southern Peloponnese www.bigfatgreekodyssey.com

To leave a message, click on the link below.

© Text and photographs copyright of the authors 2012