LAST week we sloped out of the Peloponnese for a trip to Athens, mainly to see the new Acropolis Museum for the first time. The museum, for anyone who hasn’t seen it yet, is outstandingly good, beautifully designed and the surrounding historic area of Makryannis, right beneath the Acropolis, is stylish too.

The design of the £110 million museum is inspirational, with glass floors in the main atrium area on each of the three floors and outside as well, where you can look down and see ongoing excavation work, which will take many years to complete, but one day visitors will be able to walk over ancient subterranean city streets.

This sense of completion, however, is not at all in evidence on the imposing third floor of the museum in the stunning Parthenon Gallery, where glass walls were created “to keep up visual contact with the monument” on the nearby Acropolis.

This is the gallery where the debate over whether or not the Elgin Marbles should be returned to Athens finally hits home. Until you see all the 5th century BC sculptures and frieze panels lined up, for the first time ever, together with copies of the missing items that make up the ‘marbles’ collection, and which are now in the British Museum, you don’t realise the full extent of the Elgin heist.

And even if you weren’t the slightest bit interested in the debate before, you can’t leave the museum without having an opinion, either way. If you were passionate to start with, I promise you’ll leave feeling very cross.

Nearly half of the original carved marble panels that make up the frieze running along the top of the cella (inner colonnade of the original Parthenon building) are now in the British Museum (BM) which amounts to 247ft of them out of the complete 524ft. The frieze is a fantastic portrayal of an Athenian procession and includes many dozens of horses and riders, and many of the best-preserved are the ones in the BM.

Sad sight: Copy of a horse’s head (left) on the east pediment of the Parthenon – the original is in the British Museum

Fifteen of the best-preserved carved marble metopes, that were placed high up on the external columns and depict mythical battles, are also in the BM. Seventeen of the best life-sized statues from the east and west pediments (gable ends) of the Parthenon, which are the most stunning feature of this building, depicting the birth of the goddess Athena on the east, and the contest of Poseidon and Athena for control of Athens in the west, are also in the BM. They include the gods and goddesses of Greek mythology – Helios, Dionysus, Artemis, Hestia, Aphrodite.

It is the pediments most of all that are a sad reminder of the Elgin “looting”, as the removal is called in the museum’s short promotional film, shown continuously on the third floor, or “plundering” as the museum’s guide book refers to it.

One of the arguments for the BM not returning the ‘marbles’ was that the British claimed Greece couldn’t be trusted to guard them for posterity and that Athens’ pollution problems had already eaten away at the Parthenon and the other Acropolis temples and sculptures. Yet the new museum, which has state-of-the-art laser technology for cleaning its marble artefacts (and techniques are on display in the museum), makes a nonsense of this argument.

The museum was built with the intention of one day housing all the treasures of the Acropolis, including the stolen Elgin pieces, yet with so many plaster copies on display, it just seems to be playing a waiting game, like a jilted bride hoping her faithless lover will leg it back, yet not quite believing he will. I hope Athens doesn’t have to wait forever for Britain to do the right thing. But will it?

Even the official opening of this museum in June 2009 failed to inspire a solution and ended in a strop between Greeks and the British over the return of the treasures and even saw the Queen and Gordon Brown, the then Prime Minister, withdraw from the event. Perhaps Brown, who hails from Fife in Scotland, the site of the Earl of Elgin’s ancestral home, was feeling a tad ashamed.

Lord of the Loot

Thomas Bruce (no relation to the Jim Bruce of this website, we’re happy to say) was the 7th Earl of Elgin when he took up the position of Ambassador to the Ottoman Court in Istanbul in 1799. He was given permission by the Athens government, then under the control of the Turks during the occupation of Greece, to remove a large hoard of statues and friezes, mainly from the Parthenon, that was dedicated to the goddess Athena in the 5th century BC, the Golden Age of Greek civilisation. Elgin intended to use this distinctive collection to adorn his aristocratic pile, Broomhall House in Fife, with Grecian splendour.

However, when he returned to Britain, Elgin was ill and broke and found his exploits on the Acropolis had whipped up rancour back home that even drew a passionate retort from the poet Byron who said the antiquities of Greece had been “defac’d by British hands”.

In the end, Elgin sold the ‘marbles’ to the BM in 1811 for £35,000, a handsome sum in those days, but half the amount he had asked for.

Elgin claimed he had acted in the interest of the Greeks by keeping these antiquities safe for posterity, but in fact Byron was right. While Elgin was looting the items from the Parthenon with his band of local workers, he damaged much of the remaining original works, and sometimes took only the upper part of statues, leaving the rest behind. Many pieces that were not good enough for the BM sale, as well as other items from the Acropolis, still adorn Broomhall House, where Elgin’s decendants still live.

It does all beg the question – what does Britain really gain by keeping the cultural assets of other countries, supposedly poorer than itself? It might have seemed clever when Britain once had an Empire, now it just seems cheap.

To see a short film by Costas Gavras on the disasters that have befallen the Acropolis visit www.returnthemarbles.com

Love that rock

THE Acropolis itself, or the ‘holy rock’ as the Greeks still refer to it, is the most amazing place, with a view of the the city stretching out in every direction and even creeping up the lower slopes of the surrounding hills as well.

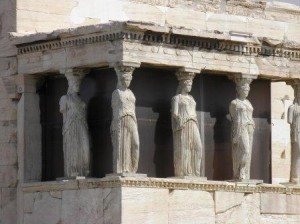

And despite ongoing restoration work to the Parthenon and cranes in evidence, workmen in hard hats, stone chisellers, crowds of tourists and stray, wolf-like dogs roaming the rock, the Parthenon still has incredible pull, even denuded of its sculptures, basically because the original design was a piece of perfection. Built to honour the Goddess Athena, this Doric temple has been hammered by more than the aristocratic follies of Lord Elgin, including earthquakes, sieges and explosions.

Tourists have probably been its worst enemy at times, and the Greeks have suddenly become quite paranoid about any desecration of its columns, and the whole environment of the Acropolis. There are many signs about the place telling you what you can and can’t do, which is quite prohibitive, including smoking, and making videos.

The sight of one young guy languishing on a bench of marble for a cute photo opportunity brought one well-built attendant with big Medusa hair flying out of her security cabin, waving her arms and admonishing the poor soul in front of a swarm of visitors. He’ll never do that again.

It’s easy to see why the Greeks still love this place so much. It has become an enduring symbol of the Greek ability to rise above strife. Like the lovely Parthenon, the country has withstood the worst of troubles: foreign occupations, wars, juntas, earthquakes, economic collapse, tourist shops still selling collarless blue-and-white cheesecloth shirts, and Demis Roussos singing in kaftans!

More on our Athens jaunt next week ...

For more information about the southern Peloponnese visit www.bigfatgreekodyssey.com

To leave a comment about the blog, click the link below.

© Copyright of the authors 2011