Horse’s head from the chariot of the moon goddess Selene is a copy of the original sculpture now in the British Museum

IN a corner of one of the rooms in the British Museum displaying the Parthenon Sculptures (popularly known as the Elgin Marbles), I could see beyond a darkened alcove a half-open door strung with some tape that read: “Gallery closed to the public.” But plainly visible through the door was the haunting image of a Caryatid statue, which once held up the porch of the Erechtheion (temple) on the Acropolis in Athens, with her five identical sisters. It’s an iconic image of Ancient Greece that everyone recognises. However, the other Famous Five reside at home, in the New Acropolis Museum in Athens. Only this one is in confinement in the BM, and has been since Lord Elgin sold his collection of looted antiquities to the museum in 1816.

While I was admiring the lady from afar, I could hear a young Greek couple chattering beside me about the off-limits statue. One was urging the other to take a picture. In the end the woman ducked under the tape and took a quick snap from the door, poring over it sheepishly on the back of her digital camera. Then the pair hurried away. What they were planning to do with it I don’t know. Perhaps to make an angry statement back in Greece to their friends about the Caryatid sister imprisoned in a dreary ‘closed’ room of the BM. I hope they do because despite pleas to bring this wondrous statue home to Athens, which happens on a fairly regular basis from Greeks and Grecophiles all over the world, this is where she’s fated to stay, it seems, along with the rest of the Elgin marbles.

The British Museum, its design ironically imitating the Parthenon with columns and an ornamental pediment at the front, continues to ignore countless requests to have the collection of sculptures returned to Athens and the debate about it rages on and on. Many celebrities and modern cultural ‘icons’ have added their tuppence worth to the debate, such as actor Stephen Fry and George and Amal Clooney, but to no avail. Why the BM won’t budge on the issue is unfathomable. It grips fearlessly to its role of guardian of the world’s cultural wealth. To be fair, while there is some altruism and vision in what it does, the assumption that it can look after other people’s cultural inheritance better than they can is outdated.

The Elgin exhibits include half the surviving items from the Parthenon, which was created in the 5th century BC during the “Golden Age” of Greek civilisation. Created as a temple to the goddess Athena, it was designed by some of the city’s great architects and built of Pentelic marble. The sculptures were entrusted to the revered artist Pheidias. They included the life-sized figures on the pediments (gable ends) of the building depicting the Olympian gods and goddesses and their struggles. The BM holds 17 of the best of these, including Helios, Dionysus, Artemis, Hestia and Aphrodite. The other sculptures are carved metopes, which sat above the columns and the frieze from the inner colonnade of the Parthenon. The BM holds 115 parts (247ft) of the frieze depicting the important Panathenaia procession with horses and riders, which took place in the city every four years.

The BM in its display notes for the sculptures explains its position and Elgin’s with these words: “The Parthenon sculptures have always been a matter for discussion but one thing is certain: his (Lord Elgin’s) actions spared them further damage by vandalism, weathering and pollution.”

This is an old chestnut and it’s partly true as the Parthenon had been damaged by earthquakes as well as during the occupation by Ottoman Turks in the 19th century, when soldiers used it for target practice and much else besides. When Elgin was given the go-ahead to remove the sculptures, in the process many were dropped and smashed. And when the BM bought them they were overzealously cleaned with bleach and other harsh substances that would have done them no favours.

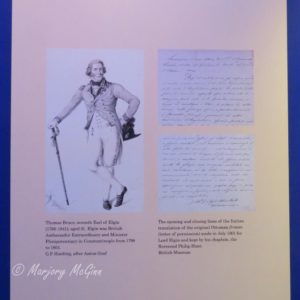

In the late 18th century, Lord Elgin was British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, which ruled Greece at the time, where he got permission to remove items from the Parthenon by way of what is now considered by many historians to be a dodgy ‘firman’, official authorisation. In the end Lord Elgin took as much as he could, amounting to half the sculptures and other items, around 220 tonnes. He also took a large number of objects from ancient Athenian burial sites, including steles, grave markers, and the funerary urns of prestigious Athenians. Why did he want it all? Not for the money initially, although he had to sell much of the collection to the BM in 1816 because he came back to Britain broke and in dire health. He got £35,000 for the collection, half what he initially wanted. But the main reason for taking the artefacts was a piece of aristocratic folly and hubris. He wanted them to decorate the ancestral pile he was building in Fife, Scotland to share with his wealthy Scottish heiress wife, Mary Nisbet.

Broomhall House today, in its vast grounds in Fife, is a grand pile occupied by the 11th Earl of Elgin, Andrew Bruce, now in his 90s. It’s a notable country seat but not a very illustrious repository for a significant collection of Greek artefacts. The Parthenon it isn’t, and neither is it Downton Abbey! In no-one’s imagination could the house be worth the desecration of ancient Greek culture. But the current family did manage to salvage something of Lord Elgin’s plunder. Not everything was bought by the BM and what remained – the inferior or very damaged pieces, and smaller items from other locations, were taken to Broomhall House and have apparently remained there.

I attempted to visit the house in 2014 for a newspaper feature on the current Earl’s collection. The house is off-limits to the public and I was barred from speaking to any of the family. It was a maid, over the phone, who finally told me that the Elgin family never discuss the marbles. No surprise there! One local Scottish journalist I spoke to however told me he’d been lucky to see inside the house and had reported there were quite a few Greek artefacts inside and in the grounds.

“They’re scattered around the house informally like bits of furniture,” he said. (To read my full account click on my earlier blog post from 2014 titled Scotland’s role in the Elgin Marbles mystery. www.bigfatgreekodyssey.com/blog/?p=1430

So Elgin’s grand folly has perhaps become the BM’s in some people’s mind. To be fair, the sculptures are prized by the BM and adequately displayed in several large airy galleries, but unimaginably so. There’s a despondent drabness about their surroundings. There were plenty of visitors the day I went, mostly Japanese, it seemed.

For them, the collection will have been fascinating, but for anyone who has seen the other half of the original collection in the fabulous New Acropolis Museum in Athens, this forlorn exhibition cannot compare in any way with what the Greeks have done. The Athens museum, opened in 2010 in the midst of the country’s economic crisis, was planned to house all the treasures of the Acropolis but mostly the Parthenon sculptures. For this it has a state of the art, purpose-built top gallery to restore and display all the surviving sculptures in the correct order, as they would have appeared on the Parthenon in the 5th century BC. The museum is built on the southern slope of the Acropolis and the Parthenon is within view through massive glass windows, giving the collection its true context.

The original chariot horse in the BM for which a copy has been made (above) to sit on one of the Parthenon pediments

Where some of the sculptures are missing – because they mostly are in the BM – they’ve been replaced with (obvious) copies. The most significant argument for the sculptures being returned and housed in the Athens museum is that this vast sequence of sculptures (and in particular the carved metopes and the frieze) have a narrative. They tell particular mythological stories of Greek gods, their triumphs and struggles, or they depict, as in the frieze, a grand procession including scores of men and riders, which is unique to Athens.

To see these items in bits and pieces in the BM makes no sense at all. The narrative is splintered, the meaning gone. To keep the two halves of the sculptural narrative separate is cultural vandalism that benefits no-one, especially the visitors.

When Lord Elgin returned to Britain with all this loot in the 19th century he was at least condemned by many of his detractors for his heist, including poet and Greek defender, Lord Bryon, who said: “The antiquities have been defac’d by British hands.”

The BM has its own take on the validity of ownership and its aims, as it explains at the Elgin display: “In London and Athens the sculptures tell different and complementary stories. In Athens they are part of a museum that focuses upon the ancient history of the city and Acropolis. The British Museum sees them as part of a world museum where they can be connected with other civilisations such as Egypt, Assyria and Persia.”

“World museum” sounds lofty but just how these antiquities might connect with the other bits and pieces of world culture also displayed out of meaningful context is left to your imagination. It would now be magnanimous if the BM gave the sculptures back to Greece so that we can all finally see them in their own historic context.

Actress and former Minister of Culture in the Greek government, Melina Mercouri, speaking at a UNESCO conference in 1982, said the sculptures “must be reintegrated into the place and space where they were conceived and created. They constitute our historical and religious heritage.” She also said: “The English have taken from us the works of our ancestors. Look after them well, because the day will come when the Greeks will ask for them back.”

The Greeks have been asking, and asking again, but sadly the British just aren’t listening. To my mind the most poignant symbol of this cultural intransigence is the lonely Caryatid statue I saw in that corner of the British Museum. She’s not holding up anything with her head as splendid as the Erechtheion temple she once graced but at least she’s still holding up – for now.

For information about the Parthenon Sculptures and some of the debate about them, click on the very informative The Acropolis of Athens site run by Greek research scientist Dr Nikolaos Chatziandreou. He also has some interesting theories on how the Scots in particular could help in the drive to get the sculptures returned to Athens.

Also: www.theacropolismuseum.gr

Books about Greece

To read my travel memoirs of life in Greece during the economic crisis visit www.bigfatgreekodyssey.com/greek-books

My first novel set in Greece, A Saint For The Summer, is a contemporary tale of romance and adventure but with an exciting WW2 thread. If follows the disappearance of the protagonist, Bronte’s grandfather serving in the Royal Army Service Corps during the infamous Battle of Kalamata, often called the ‘Greek Dunkirk’. It’s a mystery that once solved will change the lives of everyone involved.

Here’s what one reader recently wrote in an Amazon review: “Spectacular descriptions of Greece, a love affair, snippets of history, plus an intriguing storyline make this an exciting novel. I thoroughly enjoyed it.”

https://bookgoodies.com/a/B07B4K34TV

For more information about all the books please visit the books page on our website www.bigfatgreekodyssey.com

Or visit Marjory’s books page on Facebook

Thanks for dropping by. All comments are gratefully received. Just click on the ‘chat’ bubble at the top of this page.

© All rights reserved. All text and photographs copyright of the authors 2010-2019. No content/text or photographs may be copied from the blog without the prior written permission of the authors. This applies to all posts on the blog.